A brief history of how Buddhism went to Afghanistan:

Excavations of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree and others suggest that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities in the area were among the earliest in the world.

An important site of early historical activities, many believe that Afghanistan compares to Egypt in terms of the historical value of its archaeological sites.The country sits at a unique nexus point where numerous civilizations have interacted and often fought. It has been home to various peoples through the ages, among them the ancient Iranian peoples who established the dominant role of Indo-Iranian languages in the region. At multiple points, the land has been incorporated within large regional empires, among them the Achaemenid Empire, the Macedonian Empire, the Indian Maurya Empire, the Islamic Empire and the Sassanid Empire.

Many kingdoms have also risen to power in what is now Afghanistan, such as the Greco-Bactrians, Kushans, Hephthalites, Kabul Shahis, Saffarids, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Kartids, Timurids, Mughals, and finally the Hotaki and Durrani dynasties that marked the political origins of the modern state.

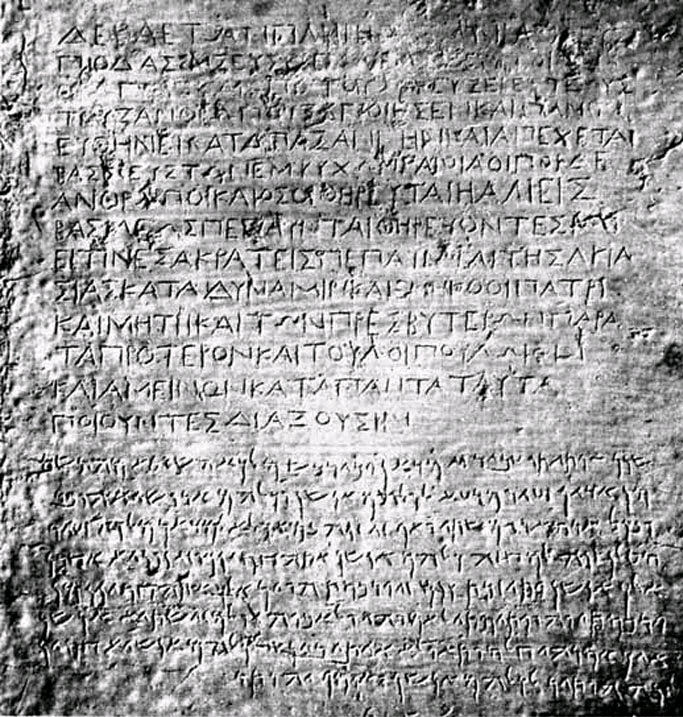

Pre-Islamic period Bilingual (Greek and Aramaic) edict by Emperor Ashoka from the 3rd century BCE was discovered in the southern city of Kandahar.

Bilingual (Greek and Aramaic) edict by Emperor Ashoka from the 3rd century BCE was discovered in the southern city of Kandahar.Archaeological exploration done in the 20th century suggests that the geographical area of Afghanistan has been closely connected by culture and trade with its neighbors to the east, west and north. Artifacts typical of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages have been found in Afghanistan. Urban civilization is believed to have begun as early as 3000 BCE, and the early city of Mundigak (near Kandahar in the south of the country) may have been a colony of the nearby Indus Valley Civilization.

One of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, Buddhism was widespread in the region before the Islamic conquest of Afghanistan

One of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, Buddhism was widespread in the region before the Islamic conquest of AfghanistanAfter 2000 BCE, successive waves of semi-nomadic people from Central Asia began moving south into Afghanistan, among them were many Indo-European-speaking Indo-Iranians. These tribes later migrated further south to India, west to what is now Iran, and towards Europe via the area north of the Caspian. The region as a whole was called Ariana.

The ancient religion of Zoroastrianism is believed by some to have originated in what is now Afghanistan between 1800 and 800 BCE, as its founder Zoroaster is thought to have lived and died in Balkh. Ancient Eastern Iranian languages may have been spoken in the region around the time of the rise of Zoroastrianism. By the middle of the 6th century BCE, the Achaemenid Persians overthrew the Medes and incorporated Afghanistan (Arachosia, Aria and Bactria) within its boundaries. An inscription on the tombstone of King Darius I of Persia mentions the Kabul Valley in a list of the 29 countries that he had conquered.

Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army arrived to the area of Afghanistan in 330 BCE after defeating Darius III of Persia a year earlier in the Battle of Gaugamela. Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire controlled the area until 305 BCE when they gave much of it to the Indian Maurya Empire as part of an alliance treaty.

"Alexander took these away from the Aryans and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants." —Strabo, 64 BC – 24 AD

The Mauryans brought Buddhism from India and controlled the area south of the Hindu Kush until about 185 BCE when they were overthrown. Their decline began 60 years after Ashoka's rule ended, leading to the Hellenistic reconquest of the region by the Greco-Bactrians. Much of it soon broke away from the Greco-Bactrians and became part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks were defeated and expelled by the Indo-Scythians in the late 2nd century BCE.

During the 1st century BCE, the Parthian Empire subjugated the region, but lost it to their Indo-Parthian vassals.

In the mid to late 1st century CE the vast Kushan Empire, centered in modern Afghanistan, became great patrons of Buddhist culture. The Kushans were defeated by the Sassanids in the 3rd century CE. Although various rulers calling themselves Kushanshas (generally known as the Indo-Sassanids) continued to rule at least parts of the region, they were probably more or less subject to the Sassanids.

The late Kushans were followed by the Kidarite Huns who, in turn, were replaced by the short-lived but powerful Hephthalites, as rulers. The Hephthalites were defeated by Khosrau I in CE 557, who re-established Sassanid power in Persia. However, in the 6th century CE, the successors to the Kushans and Hepthalites established a small dynasty in Kabulistan called Kabul Shahi.