As this article says it, "But as a Tibetan, I think elevating him to a pedestal so lofty that he is essentially disconnected from the complexities of the world’s injustices is an injustice unto itself. I don’t think it’s right for us to treat Kundun that way."Whether it's having an outdated view of women and their standing or how Tibetans in the world are today, one thing is clear, the Dalai Lama could have done so much more for people and in his twilight years, instead of making every minute count, he seems to be moving farther away from achieving realistic goals for improving the Tibetan situation.Commentary: Admiring & Admonishing the Dalai Lama His Holiness the Dalai Lama can be wrong sometimes, says Gelek Badheytsang. And that’s okay.After the Dalai Lama’s recent interview with the BBC’s Rajini Vaidyanathan, his various pronouncements about Brexit, Trump, the migrant crisis in Europe, relations with China, etc. made the rounds on media and social media. One exchange that caused much anguish and ire was his comment — which some have seen as a joke — about how the next Dalai Lama, should they be a woman, must be physically attractive.

The indignation was instant. Many perceived and called out overt sexism in that remark, and proceeded to “cancel” His Holiness. Others expressed disappointment: if a celibate and renowned monk could say such a thing, and in front of a female journalist, then what are we to expect from regular men?

There were also admirers, Tibetans and non-Tibetans, who rose up to clarify and contextualize his words on his behalf. “If you watch the full BBC video interview you can see how the blog article by Rajini Vaidyanathan adds spin, removing the actual context and laughter,” tweeted Buddhist teacher Robert Thurman, a student and friend of His Holiness.

This is the milieu we find ourselves in: people rushing to defend the honor of a champion of non-violence, but with aggression or even violence in their minds.

Tenzin Mingyur Paldron, a PhD candidate, was more poetic (and pained) in his essay: “[…] when I look at him I don’t see a Nobel Peace Prize laureate or a celebrity. I see someone who, as an adolescent, was given the responsibility to lead his people through foreign invasion and decades of ongoing colonialism.”

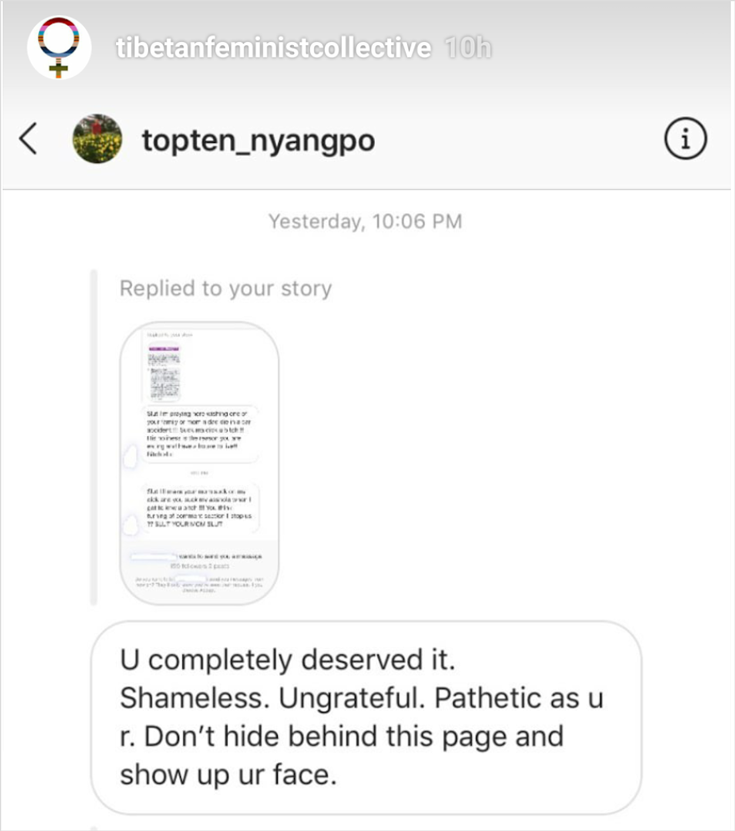

Some were pronounced in their anger towards the backlash, questioning Vaidyanathan’s journalistic integrity (not unlike what professor Thurman did). They even went as far as to target Tibetan women and groups like the Tibetan Feminist Collective, who posted a thoughtful critique of His Holiness on Instagram following the interview and had to subsequently delete it when they were flooded with comments punctuated with rape and death threats. There were messages like the one below from a monk who defended those comments condoning sexual assaults on Tibetan women who dared to question the Dalai Lama’s feminist credentials:

This is the milieu we find ourselves in: people rushing to defend the honor of a champion of non-violence, but with aggression or even violence in their minds.

Maybe this was all a big misunderstanding. Maybe it was a lesson for us in being more cognizant about the limits of gender and political discourse with someone of a different language and times. A tempest in a social-media teacup.

The Dalai Lama’s office has since then posted an official mea culpa. His Holiness meant no offense, the statement assured. It even referred to a Vogue magazine interview that took place almost 30 years ago as a way to contextualize his remarks.

I personally thought the conversation was fair and Vaidyanathan’s questions incisive. Yes, His Holiness’s remarks about the physical appearance of a female Dalai Lama or refugees in Europe were problematic. The fact that he espoused those sentiments to a woman and daughter of immigrants in the U.K. belies this notion that he was somehow being extra thoughtful about his interlocutor.

Beyond His Holiness’s prognostications about female Dalai Lamas, I wish Vaidyanthan had the time to pick apart the inconsistencies and contradictions inherent in other parts of her interview. Why would someone like him, who constantly emphasizes the oneness of humanity and reminds us that he is a global citizen, be fixated on European state borders? It shouldn’t matter if an impoverished refugee is a Muslim or African, and whether they choose to stay in their host country, just as it shouldn’t matter if a female Dalai Lama is physically attractive or not.

The Dalai Lama tweeted on April 19, 2019, “Because anger and hostility destroy our peace of mind, it is they that are our real enemy. Anger ruins our health; a compassionate attitude restores it. If it were basic human nature to be angry, there’d be no hope, but since it is our nature to be compassionate, there is.”

But how can someone compassionate reconcile that kind of belief with the fact that there are infants currently locked up in overcrowded cages on the U.S. southern border? How is it the fault of the Pacific Islanders that their homelands are disappearing before their eyes due to rising sea levels from climate change that is disproportionately driven by first-world countries? Are Uighurs’ and Tibetans’ detentions in concentration camps by China a problem that they created themselves? Is the onus on the Indigenous peoples here on the American continents to not get angry about the colonization of their lands?

And so on, and so on.

Tibetans have a raft of titles for His Holiness: tsawey lama (root teacher), chinor ghongsa kaybgoen chenpo (jewel for all), gyelwa rinpoche (victorious jewel), gongsachog (supreme being), yeshey norbu (jewel of wisdom), etc. The most commonly used designation (this is true for me at least), might be Kundun, which roughly translates into “a god in front of us; an idol in flesh.”

On the eve of his 84th birthday, it would be ludicrous for someone like me to tell someone like Kundun how he should think and speak. But as a Tibetan, I think elevating him to a pedestal so lofty that he is essentially disconnected from the complexities of the world’s injustices is an injustice unto itself. I don’t think it’s right for us to treat Kundun that way.

Perhaps what Kundun needs to do is not speak less, since his voice is as urgent as when he won the Nobel Peace Prize 30 years ago, but speak in a way that’s more attuned towards the plight of the subaltern today. I do wish that Kundun would speak more forcefully about the insidious impacts of colonialism and racism, and about how Buddhism as a way of life and philosophy is fundamentally incompatible with capitalism and neoliberalism.

Toward the end of the interview, Kundun talks about how he always admired the BBC. “One reason I am convinced [I like] BBC, is [because] BBC is critical of your own government, and report in a very balanced way. Not like Chinese media, [which is] 100 percent pro [government].”

It would behoove those of Kundun’s defenders to actually listen to this interview in full and contemplate what was said. It’s okay to say Kundun is wrong sometimes. It is actually, for the sake of Tibetan Buddhism and our freedom, necessary.

https://www.lionsroar.com/commentary-admiring-admonishing-the-dalai-lama/