A TIBETAN IDENTITY CRISIS (1996-1999)

© by Ursula Bernis

PART III – ATTEMPTING TO MAKE SENSE

The Dalai Lama said about the Dorje Shugden conflict, “This is not my issue: it is the issue of Tibetan religion and politics…” I will follow this lead and examine the uniquely Tibetan mix of religion and politics primarily as it pertains to the Dorje Shugden issue in the hope of disentangling some of the religious from the political explanations. Their indiscriminate mix has caused endless confusion and misuse. I see this to be the true source of the problem. Thus, I am treating the Dorje Shugden conflict as the most obvious symptom of a larger identity crisis I believe will not begin to be solved until the currently instituted political practice of merging religion and politics has been adequately scrutinized.

My attempt at clarification tries to show the complex historical juncture in which any Tibetan issue must be considered. Since the Dalai Lama plays such a central role in the lives of Tibetans, especially since coming into exile, and in taking their religious traditions into the twenty-first century, he figures prominently in this writing as well. He has taken an active role in the political future of Tibet and in the social transformation of his people. It should not be surprising that the Dalai Lama, in that context, is a prisoner of historical forces just like everyone else and does not always look as perfect as a religious person sees him or would like him to be portrayed.

I hope this will not be interpreted out of hand as demonizing or an out-right attack on the Dalai Lama. At least, it is not my intention.

My approach distinguishes between three different aspects of the Dalai Lama: the religious figure, the politician, and the media created celebrity. The relationship between Buddhist master and disciple is private and cannot be legislated. It resists public discourse beyond the right to freely choose and to maintain such a relationship. This aspect of the Dalai Lama, the object of people’s faith, is not the subject of this book.

As an active public political figure, on the other hand, the Dalai Lama is subject to criticism as are all political leaders whose main function is to compromise and to negotiate between different political factions. I believe criticism in politics is not so much based on morality than on law, contracts, and principles, a distinction also often lost in American politics. Thus, when the Dalai Lama uses his political office to universally institute his personal rejection of a religious practice, as is the case with Dharmapala Dorje Shugden, he lays himself open to such criticism.

Historically, Buddhist masters have disagreed on a great number of religious practices, but only the Dalai Lama has the political power to enforce his preferences.

The fact that some Tibetans did not go along with this type of politics could be seen as a sign of health rather than weakness.

Finally, the Dalai Lama as pop icon gives him a modern mythical status that seems in seamless continuity with the institutionalized myth at the base of the Tibetan national identity. Even though this modern myth-making has helped turn Buddhism into a household name, globalizing that profound religion within the entertainment driven media culture propagates a new version not necessarily accepted by all practicing Buddhists because it is perceived to be inimical to the religion’s depth dimension. The supreme political status of the Dalai Lamas since the Fifth has naturally lent their religious words different weight from other spiritually equally accomplished Lamas. However, the process of transforming such a religious public figure into an international celebrity also made possible its political appropriation in ways previously unthinkable. Since the Dalai Lama as pop icon is now the most well-known Buddhist leader worldwide, “the face Buddhism wears in the West,” the political appropriation of his celebrity status necessarily has far reaching effects on Buddhism too, something not yet adequately thought through.

The Tibetan identity crisis to which the Dalai Lama is responding is largely a result of a society having to face a secular world in which religion does not play the same role as it did in traditional Tibet. To fill the void and in order to meet the many different political and social demands, a new Tibetan self-image had to be constructed. Tibetans in exile are passing through a social mirror stage for the first time in their culture’s history. They had no need before to see themselves reflectively through the eyes of another culture – politically the geographical distance helped maintain the isolation and the religious cultural influence extended mostly outward from the center, Lhasa.

This self-contained status changed dramatically when Tibetans were thrust into a multi-cultural world. By the 1990′s Tibetan culture had increasingly been scrutinized by those intensely interested to the merely curious and from all around the world. Today, Tibetan culture exists more in front of cameras than elsewhere. In this, Tibetans mistakenly see the guarantee for its survival. We know that the self-conscious creation of a public image does not follow the same process as cultural transformation. The gap between them is at the center of the Tibetan identity crisis in which Dorje Shugden has played such a surprisingly prominent role. He has served as a scapegoat for all unwanted cultural, political, and psychological baggage. Thus purifying many of the undesirable elements from the newly constructed Tibetan image made it more presentable to the rest of the world.

The image of an exotic, yet compassionate, culture was the one commodity Tibetans could trade in the global market place. The need to eliminate important cultural distinctions in the service of a uniform global Tibetan cultural image explains to some extent how Dorje Shugden came to play such a crucial role in the current Tibetan identity crisis.

The success of the process is measured by how thoroughly the Tibetan exile government and the social groups that constitute it pursued — and continue to do so — the demonization of Dorje Shugden so that his name elicits instant deep hatred, revulsion, or, at best, anxiety and intense discomfort.

Name recognition of Dorje Shugden is now 100% in the Tibetan exile community. Unlike Nechung, the protector who speaks through the State Oracle, whom every Tibetan has heard of since he is also used for functions of state and politics, the name of Dorje Shugden had not been much in public circulation before 1996.

There was no reason to do so even by those who relied on this Dharmapala, since the practice was maintained within the religious domain of esoteric Buddhism. It is customary among Gelugpas to discuss such issues only in appropriate fora, not among the public in general as it became routine since Dorje Shugden was made a political issue.

I will summarize here, before discussing them in more depth below, the common reasons the Dalai Lama and his government have given for their ban of Dorje Shugden, which turns out to be far more comprehensive than the usual meaning of that word. These reasons were used to create a universal perception of the evil-spirit-scapegoat. In this they were successful and, solely with this aim in mind, they even have some coherence. However, they have nothing whatsoever to do with a religious explanation or the view of the people involved in the practice of Dharmapala Dorje Shugden and their reasons for relying on him. After stating the most commonly cited reasons, I will abbreviate the most salient reason why the government’s basis does not amount to a satisfactory explanation for a large number of Tibetans.

(1) Claim: Dorje Shugden harms the cause of Tibet.

Objection: The cause of Tibet means freedom to Tibetans while their leader has long given it up. It is difficult to see how, then, Dorje Shugden could harm it.

(2) Claim: Dorje Shugden harms the life and health of the Dalai Lama.

Objection: The Dalai Lama is a manifestation of the Buddha of Compassion and cannot be harmed by spirits. It is difficult to see how Dorje Shugden, even if he were an evil spirit, could do so, according to Buddhist doctrine.

(3) Claim: Dorje Shugden harms the institution of Dalai Lama.

Objection: That institution, i.e. the Ganden Potang government, is history. It lacks any legal basis or official recognition at this point. It exists today only in the person of the Dalai Lama. How can Dorje Shugden then harm that institution? The future of the Dalai Lama’s personal religious lineage is put in question only by the Dalai Lama himself, not Dorje Shugden.

(4) Claim: Dorje Shugden is sectarian.

Objection: All Tibetan Buddhist traditions are sectarian. There is no reason to single out Gelugpas if it were not for their historical proximity to political power.

(5) Claim: Buddhism degenerates into spirit worship as a result of propitiating Dorje Shugden.

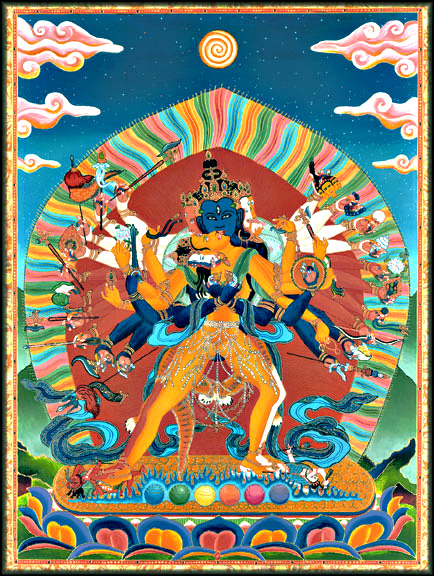

Objection: Buddhists who rely on him do not see Dorje Shugden as a harmful spirit but a Dharmapala whose nature is the Buddha of wisdom. If the Dalai Lama were concerned with Buddhism degenerating into spirit worship why is everyone else (including his government) permitted to worship them?

(6) Claim: Precedent: the Fourteenth Dalai Lama cites the Fifth and Thirteenth, as well as two or three other influential Lamas as having banned Dorje Shugden.

Objection: The historical references are problematic in each of these cases. At the very least, they are open to interpretation, which still puts in question the Dalai Lama’s dogmatic stand.

(7) Claim: Dorje Shugden harms Nyingmapas and practitioners of other traditions.

Objection: A Dharma protector of a particular tradition protects that tradition, it does not attack others. This goes for all traditions. Why apply this mistaken view to only one protector?

(8) Claim: Dorje Shugden destroys those who rely on him.

Objection: The function of all protectors is to prevent the practitioner from going against his or her vows and the Buddhist way. If anyone is harmed, the cause is a violation or other negative actions, not the Dharma protector.

I will try to show in this part of the book that the dramatized, widely propagated nature of these claims – especially the most serious ones of harming the cause of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, and sectarianism – has no basis in reality. They are for the most part projected fears hardened into political slogans. I think it is preposterous to believe this campaign of hate has anything to do with religion.

One has only to look at the other bizarre charges raised indiscriminately and universally against Buddhists who rely on Dharmapala Dorje Shugden, such as murder, assassination attempts and designs on the Dalai Lama and other government officials, treason, and all sorts of betrayals and evil actions — dealt with below in the section “War on Words” — to know that the conflict takes place in the vicinity of political wrangling for fame, power, and influence, not religion.

This brings me to the difficulties I found in writing about this issue; some of which I would like to touch upon here. For example, the above claims are usually made without any other context than an appeal to the absolute authority of the Dalai Lama. Looked at from another perspective, their fragmentary nature bring into focus the lack of a coherent rational framework. Hence, the problematic issue of the subject matter itself — demonizing Dorje Shugden to create an effective scapegoat — limits my approach.

Considering the source of the conflict, it is not difficult to see that the subject defies a simple, straightforward analysis. How can one reason about a problematic issue that has its origin in prophesies from invisible beings speaking through oracles? The situation is so obscured by layers of ancient and modern myths of power that it has so far resisted any reasoned explanation. The irrational response to the ban even by Western Tibet experts in their attempts to justify the Dalai Lama’s actions and the mostly emotional content of the Tibetan experience makes the issue even more difficult to analyze.

One of the most disturbing components I found in trying to make sense of this complexly layered phenomenon is the intolerant out of hand rejection of any interpretation other than the official one. This forces anyone open-minded and inclusive into a position of having to disagree with the Dalai Lama instead of merely presenting a different perspective on an issue. It is deeply disturbing that the global Buddhism the Dalai Lama has dedicated his life to constructing rejects so absolutely any interpretation of the most learned Gelugpa Buddhist masters other than that of ignorant devil worshipers. It makes a rational approach practically impossible.

Another troubling point I found was that no overall group or organization of “Dorje Shugden followers” existed until in 1996, when the government indiscriminately declared this fictitious entity to be a “cult.” This way they lumped together a diversity of people from different geographical and cultural areas and across the social and economic spectrum and labeled them with a word absent from the Tibetan language. There was no such separate group of Dorje Shugden followers until the Tibetan government-in-exile attempted to create one intentionally in order to marginalize them more easily, according to its own documents. This makes writing about them very difficult, especially in any general way as I am doing here, without participating in the government’s strategy of casting them out of Tibetan society.

In addition, the most educated Gelugpas affected by the ban remained silent. I respect their contemporary wisdom of refusing to compete in the global market place with discussions about esoteric Buddhist subjects where they are inevitably misunderstood.

The government’s rejection of any reasoned debate about the subject condemned them to silence. From the beginning of the crisis in 1996 the Dalai Lama was determined to destroy the practice. Whether or not to continue Dorje Shugden was never subject to debate or negotiation. This type of intolerance is foreign to Buddhist principles. While a Buddhist teacher may advise the disciples not to do certain practices for religious reasons, the Dalai Lama’s political status empowered his government, made up of many social groups, to enforce it.

Hence, since a religious issue was displaced into the political domain in order to destroy a tradition, the official literature on the conflict is full of contradictions and unproven accusations. It is fragmentary and incoherent because it is primarily supported by appeal to authority in an attempt to prove the unprovable, not by facts or reasons. The Dalai Lama himself did not add anything to help find a reasonable approach to this subject. In answer to my repeated request to provide reasons Westerners could understand so that they may judge for themselves why this conflict was occurring, he talked quite emotionally about evil spirits, spirit worship, and the mental instability of Western Buddhists, hardly a rational approach.

Thus, I will limit my presentation to providing some historical and cultural background, especially leading up to the identity crisis of the 1990′s in exile, in order to contextualize the relevant material. In addition, I will focus on the medium of language in which the creation of the new global Tibetan image meant to replace the old identity plays itself out. I will try to unravel some of the religious and political meanings mixed and confused in key terms and slogans in the vicinity of the Dorje Shugden conflict; point to the use of magical realism in Tibetan political discourse; shed some light on the manipulation of the media in the service of the new Tibetan image; as well as touch on the construct of a global Buddhism currently propagated – a Buddhism determined more by market forces, the norms of the entertainment industry, and by celebrity cults than its Tibetan tradition. In the process, I hope to raise more questions in urgent need of being addressed than provide answers.

TIBETAN IDENTITY

The Tibetan identity is in crisis and in danger of losing whatever is its Tibetanness. This is the Dalai Lama’s stated concern for Tibetans inside Tibet that he says has motivated him to give up independence in favor of “cultural autonomy.” Exactly what makes Tibetans Tibetan is hard to define. To an outside observer like myself it would have to include the irrepressible sense of individual freedom, a culture specific religiosity, and the curious ability to inspire the imagination of countless people around the world.

In exile, the Dalai Lama, embodying all of these factors, became the very soul of Tibetans, their identity, and, as Avalokiteshvara, Buddha of compassion, their myth of origin. In holding on to the one institution left from the old Tibet, they often do not acknowledge the changed realities the Dalai Lama has to deal with in exile. The myths revived are now in danger of ossifying into a utopian ideology of cultural superiority that sees Tibet not as a country but as the realm for the revival of the spirit, a zone of peace between China and India. In as much as the Dalai Lama is symbolic of the undying flame of Tibet, no matter what the myth, Tibetans believe they owe him absolute loyalty and allegiance now more than ever.

The Dalai Lama is the one correct role model for Tibetans; beyond criticism, beyond reproach. Reflected in the behavior especially of young monks across India is the Dalai Lama’s un-Tibetan mix of “simple monk” image and international jet setter.

The Mahayana goal of enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings is changing to a public persona teaching in the West to make the plight of Tibet known to the world. This striving is pervasive and has become part of the exile cultural fabric reflecting the unconscious identification with the His Holiness and legitimated by his celebrity status, the highest goal visible to the image culture. Many monks even imitate the emotional range of the Dalai Lama’s verbal expressions that glide effortlessly from the deepest low to the highest high in a matter of seconds, his elaborate hand gesturing influenced by Indian body language, their use of his pervasive terms, like universal responsibility and tolerance, to cover their own often un-monk like behavior.

The more the Dalai Lama’s Western persona as champion of democracy, innovation, non-violence, science, ecumenism, new age universalism and global interrelatedness is perfected and celebrated worldwide, the older the myths seem that are revived by Tibetans in India and Tibet. As Buddhism is transformed into a global phenomenon, pre-Buddhist beliefs are resurrected among exile Tibetans on a larger scale than before.

There are plenty of myths perpetuated within Buddhism as well — some perhaps more necessary than others. Debunking the myth of Shangrila has become the academic fashion of the moment. Tibet related intellectuals have found that the West projects its own fantasies, needs and desires onto “Tibet.” This is considered unique, as if we did not project our own desires and fantasies onto other countries, like China, for example, or as if Tibetans, Indians, Indonesians, and many others did not project their fantasies of the “American dream” onto the United States, each according to need.

Since Tibet is currently fashionable, it is also fashionable to deconstruct it where, strangely, Tibet is assumed to be an empty projection screen, perhaps a synonym of a modernity whose mythic content has been sidelined. Ironically, Tibetan Buddhism originally became so popular because it was a religion with its own world that had not yet been subjugated by the media empire. A window opened on a genuine otherness accessible to Western emotional experiences through the universality of Buddhism. Since it has become a media phenomenon, the Western fascination with Tibet is described almost exclusively as a mere projection of its own spiritual needs and fantasies rather than a legitimate exercise of the cultural imagination in pursuit of something lost from its own history. The search for Shangrila has become utopian which throws a shadow on the truth of Buddhism and the inner journey its traditional Tibetan versions could provide.

“Shangrila” is considered a distortion of Shambala, the mythical land of the kings that are also knowledge holders (rigs.ldan) of the Kalachakra tantra. The first king of Shambala to have received the Kalachakra empowerment from the Buddha “returned to Shambala, wrote a long exposition of it, and propagated Kalachakra Buddhism as the state religion.”

The myth, according to Tibetan sources, tells that the last king of Shambala will defeat the “barbarians” in a great war of apocalyptic proportions after which Buddhism will flourish again for another two millennia. The Kalachakra tantra came to Tibet from India through several transmission lineages from the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries long before the Ganden Potang government was established. It was first practiced by the Panchen Lamas, especially the third, and from the eighth Dalai Lama it was performed by Namgyal Monastery, the private monastery of the Dalai Lamas.

A Dalai Lama gave Kalachakra empowerment to large groups of people traditionally no more than five times, since it is meant for attendees to establish a karmic connection with a future world Buddhist revival believed to be the fated task for Shambala’s king. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama has performed Kalachakra empowerment many more times and in different parts of the world from Tibet, India, Mongolia, to the United States and Europe. Hundreds of thousands of people attend these mass events to which Buddhists and non-Buddhists flock.

The one in Bloomington, Indiana, in August 1999, was organized by one of the Dalai Lama’s brothers, Professor Norbu, with the help of many different groups, including Christian, interfaith and non-religious social groups. Its theme is world peace and to “transform the millennium.” “The Kalachakra, the most revered of all Tibetan Buddhist rituals, is open to persons of all spiritual traditions and beliefs,” according to the advertising company handling the publicity for the event, except for Buddhists who rely on Dorje Shugden.

It is clear to anyone from the absolute stand the Dalai Lama has taken for the past three years of refusing anyone who relies on Dorje Shugden to attend his public teachings and empowerments that they are also excluded from the Indiana Kalachakra affair. However, Professor Norbu and his son, organizer of the event, seemed surprised that Buddhists who rely on Dorje Shugden do not feel welcome, according to an article in the Village Voice. As required by public relations, the Norbus contend “that all faiths are welcome at the Kalachakra.” A month later the Dalai Lama confirms at a press conference that Buddhists who rely on Dorje Shugden cannot come to the event open to people from all faiths and atheists alike.

The myth of the king of Shambala now reigns over vastly larger parts of the world than he does in his mythical kingdom. Professor Robert Thurman, a spokesman for the Dalai Lama, identifies him with the Kings of Shambala not only from the point of view of personal religious practice, as mostly taught in Buddhism, but also in millennial fashion. He outlines Tibetan history through the Kalachakra mandala and criticizes scholars attempting to find a model to cut through the mythic overly to knowledge about Tibet as “driven by their deeply ingrained sense of the intrinsic superiority of the West and the historic inevitability of its form of modernity.”

When describing the Kalachakra emblem on a hat a Manchu emperor had offered to a “a high Lama in government service, …such as the Dalai Lama or the Panchen Lama,” he says, “The Kalachakra or Wheel of Time Tantra …[is] especially connected with the Tibetan calendar and sense of history or destiny, as it contains the famous prophecy of Shambhala. [The emblem] was regarded as a powerful talisman, signifying that the Ganden Palace government based in the Potala was authorized to maintain Tibet’s connection with the Kalachakra eschatology. ” Authorized by whom? The Manchu emperor? The legitimation of the Dalai Lama’s claim to the prophesy of Shambala, that is, to the future world leadership of Buddhism in the form of Shambala’s king victorious in the apocalyptic war with evil — Thurman here brings it into historical proximity with a Chinese emperor — is worrisome.

It is however not history in the common sense of that word which is the issue. It is rather a Tibetan identity in search for a country. The Kalachakra myth provides the Dalai Lama, invariably referred to as God King in the press, with a mythical country to his now mythical Ganden Potang government. Yet the Dalai Lama is also hailed as a modernizer. This is just one of the many contradictions inevitably surrounding someone of such legendary status.

Most Tibet experts other than Thurman currently claim that the myth of Tibet is merely in the eyes of the beholder. That leaves Tibetans out of the picture altogether and makes totally acceptable the view of the Dalai Lama as modernizer. If, indeed, the myth of Tibet was merely the projection of naive Westerners who have lost the claim to their own imagination as a result of demythologizing Christianity and other Euro-centered religious belief systems, then just look who helps feed that myth! The image of Dalai Lama as a modernizer seems to obscure the wider panorama on this issue.

Regardless of whatever modernity the West reads into the exile community on the basis of the Dalai Lama’s image, the voice of reason in political discourse and social dialogue is very hard to find. It is conspicuously absent not because it does not exist, but because it is silenced. The ground for the Tibetan identity in exile is the Dalai Lama myth, not a country; a culture, not workable institutions; devoted imitation, not rational discussion; morality play, not analysis and reason. With the Dalai Lama believed to have a monopoly on the truth rather than power, free speech and public debate become superfluous in the exile community, free participation in the political process impossible. In a crisis, a few words by the Dalai Lama repeated as slogans eclipse any rational public discourse.

SHIFTING POWER BASE IN EXILE

From Politics back to Religion in a new Mix

The cultural and political upheaval for Tibetans in exile since 1959 naturally caused an unsettling identity crisis of unparalleled proportions. The many shifts and changes in their lives brought to the surface old conflicts and created many new ones. The mechanism to deal with them adequately was simply not in place at a time when struggle for survival took precedence over all else. The strategy was to line up everyone behind the Dalai Lama, seen as the single legitimate symbol of the Tibetan nation.

The problem however was that without adequate new structures to deal with the changed social and political realities, old habits prevailed. The culture could not transform itself and started to become hollow after only one generation in exile. This merely accentuated the identity crisis erupting for the first time large scale in the 1990′s. The Dalai Lama also had to reinvent himself, and the old myth of the Ganden Potang government with the Dalai Lama at its center had to be transformed into a modern one. This became the main Tibetan project in exile. The exile administration started to use the term Ganden Potang government again in the 1990′s with the official reinstatement of the union of religion and politics in 1991.

The adoption of the first Charter for the Tibetan exile administration in India in 1991 actually grew out of the political need to include solutions to Tibet’s status other than complete independence. The draft constitution for a future Tibet of 1963 was explicitly committed to independence on which the Dalai Lama reversed himself in 1987-88 (Five Point Peace Plan and Strasbourg Proposal). The new charter was hailed as a great advance in the experiment with democracy – the only reason given publically for its adoption — because it increased the number of elected deputies. Yet they insisted on keeping in its preamble the term unity of religion and politics, the defining feature of Tibet’s historical Ganden Potang government, as the mandate of the new exile administration. This was out of respect for His Holiness, who accepted the devotion of his subjects without overriding their decision.

The Dalai Lama as Dalai Lama is part and parcel of the Ganden Potang government. It must have been inconceivable to the officials to keep one and reject the other. A rejection of the Ganden Potang also meant the rejection of the Dalai Lama, the very symbol of Tibet. Had the Dalai Lama pressed harder for a secular government at the time, as he had initially proposed, the experiment with democracy might have taken a different turn.

In this carefully choreographed dance with the Dalai Lama, a conservative element took over foreshadowing the increasingly militant positions Tibetans would take especially on controversial issues. Why did Dharamsala revert to the basis of the Ganden Potang government at a time when it claimed to modernize? In Tibet the main power base for this government was the landed aristocracy, the great monastic universities around Lhasa and the landed Gelugpa monasteries across the country. Where before in Tibet Gelugpas controlled the government, now, in exile, the government controls Gelugpa, and the other religious traditions are demanding a larger share of the political pie. Either way, the unity of state and religion is upheld.

The only difference is that today, inside and outside Tibet, the respective governments interfere much more in the religious aspect of the Gelug tradition which has become politicizing it in unprecedented ways. In exile, the person of the Dalai Lama, the power of the name and institution inherited from Tibetan history, as well as the myth carrying his fame have become the power base for exile Tibetans in the absence of a country, independent economic base, legal status to their government in India and abroad.

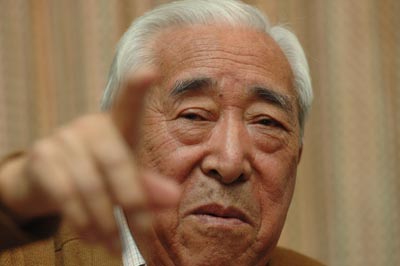

Intentionally and carefully crafted in the early days of exile from 1962-1967 by the Dalai Lama’s brother Gyalo Thondup, His Holiness’ persona was hailed as the only savior of Tibet and its cause. The exile government distanced itself early on from politically educated Tibetans, since they had been the elite in Tibet, and replaced them with their servants, according to Professor Dawa Norbu. Since then, not only the old elite but also the young, educated new elite — especially intellectuals like Jamyang Norbu, Tashi Tsering, Lhasang Tsering, Sonam Chopel, and late K. Thondup, who were pointing in a direction of separating religion from politics — has been excluded from political power. Instead, officials subservient and loyal to the Dalai Lama’s family were said to have the best chance of succeeding in the Dharamsala government.

The main focus is on His Holiness. Samdong Rinpoche underscores the savior image of the Dalai Lama when he says that the only reason why Tibetans are tolerated in India is because of “the person, not the institution, of this Dalai Lama.”

Children growing up in exile were reminded at every moment that their lives, sustenance, livelihood, and education came to them by the kindness of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. They were educated into an unquestioned acceptance of his role and so believed this literally as did the older, religious minded Tibetans, whose proximity to the Dalai Lama was now much closer than it had ever been in Tibet. A whole generation grew up in exile believing in the Dalai Lama as a God who provides everything for his children rather than a Buddha, a guide to enlightenment. Developing an idea of the Dalai Lama as God might have been come from the influence of Indian culture on Tibetans as well as the Christian model that played such a large role in the education of the Tibetan elite in exile.

The idea that the sole source of every small and big happiness of Tibetan existence is the kindness of the Dalai Lama and that they were deeply indebted to him was thoroughly inscribed into the cultural fabric in exile. In a touching display of submission, the 1999 official Tibetan calendar, published by the Tibetan Medical Institute in Dharamsala, lists December 10th as the “coronation day” on which the Dalai Lama was crowned with the Nobel Peace Prize.

This idolizing relationship Tibetans developed with the Dalai Lama in exile is quite different from that of the more independent minded people of old Tibet. The image of the sole savior of Tibetans is a construct fashioned out of political necessity with religious content. For political reasons even the accomplishments of other Tibetan Lamas were appropriated by the official religious establishment in Dharamsala.

All good things were attributed to His Holiness starting in the 1980′s not necessarily out of religious devotion but out of an overriding political urgency. When today the Dalai Lama’s representatives lecture other Tibetan Lamas teaching in the West on the kindness of His Holiness, i.e. that they owe him everything since, according to them, Dharma would not exist in the West without the Dalai Lama, they unwittingly tell the story in reverse30. Buddhist teachers from Japan, Vietnam, Shri Lanka, etc., and Tibetan Lamas from all schools laid the foundation for Buddhist development in the West. They made possible the later success of the Dalai Lama.

A well functioning net of Tibetan Buddhist organizations was already established when the Dalai Lama taught in Europe for the first time. His first visit to the United States was not until 1979. When the Dalai Lama says of himself today, “The institution of Dalai Lama has become the guardian of Tibetan Buddhism,” one wonders why a politicized institution such as that of the Dalai Lama with his Ganden Potang government and its failure to resolve on any level the political task with which it was entrusted should be seen as being any better qualified to serve as guardian of Tibetan Buddhism than the hundreds of other equally realized masters of Tibet’s different Buddhist traditions who are working as hard, if not as famously, at the common task of saving their religion outside of the domain of active politics.

The carefully crafted image of the Dalai Lama as religious leader the world knows today, popularized with the help of political world leaders and Hollywood since late 1980′s, became the repository for all Tibetan aspirations and hope. It provided a model for a new Tibetan self-image and identity.

The basis for the successful Dalai Lama image as the sole savior for exile Tibetans and later its globalized version was to a large extent Tibetan independence but then, in the 1990′s after many political failures, it shifted back primarily to religion. In the earlier exile days the Dalai Lama was not permitted to make political statements in India. The world did not acknowledge Tibet’s existence as an independent country. He received his first visas abroad in the late seventies only on condition of refraining from engaging in political activities or making political statements.

Whatever political aims Tibetans advanced at that time, they had to be hidden behind religious discourse or worked through local organizations. This created a most distressing situation for Tibetans almost forcing the Dalai Lama into mixing his religious and political pursuits in new and unprecedented ways. When exile Tibetans made their first contacts with Tibetans inside Tibet in the late 1970′s they became painfully aware of the scope of Chinese destruction in Tibet.

The reality hit them that there was almost nothing left of their culture and way of life to which to return. At that point the call for independence became more loudly heard beyond the exile community. The idea of independence became a powerful unifying factor for Tibetans with the Dalai Lama at the helm of this movement. In the eighties, the free Tibet movement gained momentum and became visible worldwide. Tibetans became more vocal and stated their political aims more freely.

The Nechung oracle’s continued prophesies from the early 1980′s onward of freedom and the exiles’ speedy return to a free Tibet were taken absolutely literally by almost every Tibetan. Later, in the 1990′s, when it became apparent that these prophesies had not come true, the government’s oracles started to blame Dorje Shugden for its failure and, with the unfulfilled expectations of the Strasbourg proposal (1988) to open any productive dialogue with the Chinese, the power base shifted back to religion.

When in 1988 the Dalai Lama in a speech to the European Parliament, later called the Strasbourg proposal, reneged on the commitment to independence in favor of Tibet as a zone of peace under the suzerainty of China, most Tibetans were reluctant to criticize this proposal openly, especially since it was presented to Tibetans then as a temporary solution with complete independence still as the final goal. Most Tibetans, especially those who today demonstrate in capitals throughout the world for Tibetan freedom, still explain away the ever-widening gap between the Dalai Lama’s political statements and his people’s beliefs in independence on religious grounds.

“His Holiness knows best what is needed in the long run,” they say, “He knows everything.” However, after Strasbourg, the idea of independence as the main focus for Tibetan unity disintegrated and the shift back to religion was the only possibility left to the exile leadership to maintain its control over exile Tibetans everywhere in the world. However, this religion could clearly not be the Gelugpa tradition, the most powerful religion of old Tibet to which the Dalai Lama also belonged. It had to be a new state religion under the leadership of the Dalai Lama and in a form that could be endorsed by the other Tibetan Buddhist schools as well.

The older traditions in Tibet (not in exile) had been marginalized by Gelugpa’s popularity and political power. This was perhaps more true of Nyingma, which incorporated non-Buddhist practices and beliefs mostly from Bön, than Kagyu and Sakya, although hundreds of Kagyu monasteries had been destroyed or converted to Gelugpa when the fifth Dalai Lama established his rule. The Nyingmapas have long led the vociferous anti-Gelugpa rhetoric. Gelugpas were often totally unaware that there was a Nyingma-Gelug difference, as is often the case for those in the majority.

Interesting here is that Nechung is of Nyingma origin, and Dorje Shugden is mostly Gelugpa, although relied on by Sakyas as well. I see the source of the old problematic between Nyingma and Gelug, which is today blown way out of proportion, situated in the cross between religion and political power.

I believe the political misuse of religion is the source for sectarian conflict in Tibetan Buddhism rather than their legitimate doctrinal differences, as is implied today in the denigration of the Gelugpa lineage and its masters protected by Dorje Shugden as inherently sectarian.

However, the conflict erupted when the shift from a more political focus moved back to a form of religion as the dominant power base, inevitable after all the political failures. To be sure the new form of Buddhism was a politicized version of a religion that did not exist in Tibet.

As a power base for the Ganden Potang government and its administration in exile, it had to give at least the appearance of representing everyone even if the integrity of individual traditions had to be compromised.

While the issue of independence had split the exile community in India and Nepal, with many groups and individuals still firmly committed to Tibetan freedom, at least in principle, the Dalai Lama and his project of saving Tibet’s unique culture, much of which is religious, was embraced wholeheartedly. Power consolidated in the person of the Dalai Lama became absolute. It was publicly legitimated again and again by ancient protectors speaking through oracles, the ultimate court of appeals in which the Tibetan people do not have a voice.

Consulting oracles was something the Dalai Lama had strongly criticized early on in his exile days. Attached to it was the advice to give up such practices in favor of more modern ones, like “meditation,” not common among Tibetans for whom “recitation” is the most prominent practice and the rituals connected with their belief system.

Most older Tibetans, who considered a little too fast the Dalai Lama’s “modernizing” pace started in the 1960′s — i.e. his disapproval of the widespread Tibetan practice of relying on major and minor oracles, of making traditional offerings, large monasteries, extensive rituals, etc., which make up a large part of “Tibetan culture” – were now surprised about the renewed popularity of oracles and elaborate government rituals in the 1990′s, their scope and the oracles’ access to the Dalai Lama. Perhaps the earlier advice was meant only for everyone else’s oracles, not necessarily the Dalai Lama’s or those of the government. The following anecdote told by older Tibetans illustrates the point.

Sometime in the mid eighties, the Dalai Lama told his religious attendants to stop certain local protector practices specific to each Dalai Lama. Attached to each incarnation of Dalai Lamas is a local protector of the region of his birth place, or birth protector. Thus there are fourteen of those local protectors that require monthly rituals. His Holiness instructed to give up some of them — on grounds that there were too many — and to continue only the important ones. When in his dreams different beings were fighting, believed to have been the result of having giving up the rituals for some of the Dalai Lama’s birth protectors, he reinstated them. On the whole, the shift back to religion in the 1990′s, after an earlier disillusionment with “the novelty of modernism wearing thin in Dharamsala,” is also described as “religious fundamentalism [which] began to supersede any idea of learning from the West.”

Globalizing the new image of this politicized Tibetan Buddhism went hand in hand with the celebrity status of the Dalai Lama as a world religious leader. This began in 1989, when the Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize, and exploded in the nineties with Hollywood’s help: its celebrities and two movies featuring the Dalai Lama as main hero. The Western image culture as a power base has taught Dharamsala to construct a most efficient media machine capable of an exquisite manipulation of the press. Yet the effect of a media driven culture and the celebrity status of their Buddhist leader on Tibetans in India and Nepal, aside from the financial support it generates, is still indirect and by no means the main motivator, as Tibet scholars now seem to imply. The celebrity image imported into the exile community serves to confirm the religiously based “chosen people” status that has been part of the Tibetan national identity for a very long time.

Today, Tibetans claim to be special because they are preserving their religious heritage for the world, not for themselves. “In our work and in our cause, we are trying to be very responsible, but the world should also be responsible toward a group of people that is trying to be an example for the world.”

This makes the unquestioned epochal shift of globalizing traditional Buddhist language and images so plausible to Tibetans and their supporters in the West, who seem unaware that Tibetan culture now lives mainly in media images and in decontextualized fragments of the Dalai Lama’s speech propagated throughout the world. The sad loss of cultural content was to be expected but taking them to be the sole reality of Tibetan Buddhism even more so.

Returning to the Dorje Shugden issue as example, how could anyone possibly trump the following statement by the Dalai Lama made in Germany in May 1998, concerning Buddhists who rely on Dorje Shugden, “Whoever fights against the Shugden spirit defends religious freedom. I compare this definitely to the Nazis in Germany. Whoever fights them, defends human rights, since the freedom of Nazis is not freedom.”

Since no distinction was ever made between Buddhists who rely responsibly on Dorje Shugden and those who might misuse the practice, the Dalai Lama’s statement would thus include all the great masters who believed Dorje Shugden to be a reliable Dharma protector. The mentors of the Dalai Lama himself, who transmitted hundreds and hundreds of the Buddha’s teachings to him in a purely religious context would thus be like Nazis, unworthy of freedom.

With such statements by the Dalai Lama and the widespread literalist belief in the truth of all his statements regardless of context, how can anyone speak the truth about these outstanding people and be believed? How can such stigma ever be overcome? This much power has the Dalai Lama’s speech to silence.

In fact, in March 1999 the word in Dharamsala is that Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche incarnated in a ghost. I do not take rumors seriously, but in a still largely oral society they can be looked at as a barometer of the culture. Nobody from the exile government, as far as I know, has publically questioned the offense to the religious sensibilities of the many tens of thousands of Buddhists for whom those included in such statements are revered masters. If anyone did, he or she would be reviled as anti-Dalai Lama. This is one of the sad results of mixing religion and politics in a post-modern world. The Dalai Lama’s power is mostly expressed through words and even political statements are believed to be backed by the Buddha’s doctrine which values truth.

EQUIVOCATIONS

Aside from the unique power, credibility and scope of the Dalai Lama’s words, in the absence of open discussions, public debate and a free press, the complexities of linguistic conventions easily collapse into ever repeated simplistic slogans. I would like to focus on several terms frequently used in the peculiar religio-political discourse unique to Tibetans that focuses on the Dorje Shugden issue as a symptom of the larger Tibetan identity crisis. The equivocations built into notions like “the cause of Tibet,” “freedom,” “sectarianism,” “authority,” “modernization,” “accountability,” etc., emerge from the unusual mix of religion and politics.

A clear example of how this functions is Samdong Rinpoche’s use of “democracy” as interchangeable with “equality” such that equality is understood as a function of the religious mind. Considering that the Tibetan people have never exercised democratic choices concerning the major political decisions affecting their lives, the substitution of the equality cultivated by a religious mind for “democracy” is very serious, indeed. Thus, an attempt to clarify how religion and politics interact in modern Tibetan discourse becomes all the more important. Since English is the language through which Tibetan political issues are internationalized, I will examine the multiple meanings of the relevant terms that language.

Cause of Tibet

Ask any Tibetan what “the cause of Tibet” means and they will say, freedom or independence.

In general, Tibetans understand it this way. They had come into exile to escape the lack of freedom and oppression in Tibet. Even though they might not have had the same modern sense of nation and state as had evolved in Europe in the last three centuries, Tibetans had a sense of nation, country, and cultural identity tested through repeated experience with Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol aggression and as far back as the empire King Songtsen Ganpo united in the seventh century.

Even though most Western Tibet scholars do not seem to make this distinction and apply exclusively modern political concepts in their Tibet analyses, it nevertheless existed. In exile, freedom was the cause, with the Dalai Lama as its symbol, for which so many Tibetans in Tibet had been imprisoned, tortured, starved and 1.2 million said to have died as a result of Communist policies since the uprising in 1959.

Although the sibling rivalry in the Dalai Lama’s family, the most important prevailing force in the exile government, reflects the current Tibetan political dilemma with Gyalo Thondup committed to autonomy within China from the beginning and Professor Thubten Norbu to independence, Tibetans did not have any reason to believe that the Dalai Lama was working towards anything less than freedom while promoting a gradual approach of autonomy first with independence to follow.

He continued to say in 1996 in answer to the question, “Should you demand complete independence for Tibet now?” that “…I think it don’t is not the right time,” implying that when the time was right, independence would move into the foreground again, while saying elsewhere that “in the long run, I feel Tibet, which is a small, [greater Tibet was as big as Europe!] landlocked country, might get some benefits by merging with a big nation.” Few Tibetans, however, doubted their leader’s commitment to complete independence as long term goal and those with the political acuity to anticipate the problem of independence vs. autonomy were sidelined.

In 1994, after the Dalai Lama’s brother and Chief Minister, Gyalo Thondup, had made statements in Canada to the effect that Kham would be excluded from an autonomous Tibetan region within China, the Chushi Gangdug leadership tried to find some political leverage to make sure their birth place was included in the future negotiations about Tibet.

Lithang Athar, one of the leaders in the Chushi Gangdug guerilla movement that safeguarded the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet in 1959, had taken the initiative as the representative of the now regional Chushi Gangdug organization to test the political waters. He talked to a representative of the Taiwanese government — three years before the Dalai Lama went to Taiwan — and signed a joint proposal that in the future, when the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan were united democratically, Tibet would comprise the three provinces (Ü/Tsang, Kham, and Amdo) under the political and religious leadership of the Dalai Lama. He did so not on behalf of the exile government but as leader of the regional Chushi Gangdug group.

This so angered the exile government and the Dalai Lama, who internationally preaches forgiveness for even the most radical criminals and mass murderers, that he did not even accept an apology from Athar for having overstepped the boundaries of his authority in his attempt to create political leverage. Athar went to see the Dalai Lama the day after the affair had become known to the exile government to apologize for his mistake, which to an outsider seems to have been more a case of having seriously misjudged the purported democratic nature of the exile government.

Although Dharamsala often invokes democratic terms, in practice, an apology in this case, or dialogue, or a discussion was not even under consideration. In a showdown of power, a group of people from the Chushi Gangdug region, some of whom worked in the Tibetan exile government’s security office, were now put on a ballot by Dharamsala in a move to force a new election of a “non-governmental” regional group. The ballot was announced — only verbally to be sure: “Choose between the Dalai Lama and Lithang Athar,” even though this clearly was not the issue at all.

Clearly, the exile government appointed Chushi Gangdug leaders won by 99% of the vote and Lithang Athar’s house in Delhi was vandalized. The Buddha statues and holy items from his altar taken after the glass windows of the altar had been smashed. Chushi Gangdug split into two, some call it a split between old and new Chushi Gangdug, others a split between elected and appointed Chushi Gangdug because a majority of the region still favors Athar and the leadership of the old Chushi Gangdug. To these people, the cause of Tibet unequivocally means complete freedom from Chinese rule.

It is easy to verify that the cause of Tibet means freedom to most exile Tibetans. The Tibetan Youth Congress, for example, is one organization that has never retracted its commitment to Tibetan independence. It is the fastest growing social group among Tibetans claiming at least sixty-one branches worldwide. It is estimated that more than half the exile Tibetans belong to the Tibetan Youth Congress (which includes old and young people) and they are becoming more active in expressing a commitment to independence through hunger strikes, demonstrations and other visible activities.

If you ask the old monks and other people who escaped from Tibet to follow His Holiness for the sake of religious freedom, they too say the cause of Tibet means freedom which to them means independence. It has been a rallying point for Tibetans, even if many know that its reality might be far off and that forcing it would be impractical at the moment. Nevertheless, they believe, “that Tibetans must have independence if only for survival as a people.”

“Even the hope of independence is vital,” says Jamyang Norbu, “It must be remembered that it was the hope of independence that kept our exile society strong and united in the difficult early years. Many of the problems our society now faces with religious and political quarrels, decline in school educational standards, the lamentably disgraceful commercialization of our religion, cynicism in the administration, and loss of self respect and integrity among the ordinary people have definite roots in the gradual relinquishing of the freedom struggle by the Tibetan establishment during the last two decades.” Even for the diverse crowd of Western Dalai Lama admirers, the cause of Tibet means Tibetan freedom.

The only different explanation I heard was from the Office of Tibet in London. In answer to the a question concerning the meaning of “the cause of Tibet,” Tseten Samdup in official capacity of the Tibetan exile government wrote, “I think this cannot be explained in simple terms. It is more religious and spiritual debate. I suppose it is the influence of Dorje Shugden and the action that lead to it. From childhood I never heard anything good about Dorje Shugden other than [he is] worshiped for material rewards. It is also to do with trust between the teacher and student or leader and his followers. Dorje Shugden apparently came back to challenge the works of the Dalai Lama, so goes the story. I am sorry for not [being] able to shed more light onto this. Tseten.” Tibetans I asked had never heard this explanation of the cause of Tibet.

Freedom

The Tibetan freedom movement focuses on a country colonized by an invading power against the will of its people, not the liberation from samsaric suffering. The internationalization of the Tibet issue in the mid-eighties was political and politically motivated, even though Western experts in 1998 still insist that the Dalai Lama engaged in political activities merely as an appendix to his Buddhist teachings during his visits to the U.S. Every time he came to Washington (1987), or Brussels (1988), to make statements aimed at the Chinese concerning the future of Tibet, they retaliated with harsh repression and violence towards Tibetans demonstrating in support of the Dalai Lama, their symbol of freedom. Many died and were aimprisoned and tortured as a result.

It was the first time pictures and video clips of monks brutally beaten by Chinese police were seen in the Western media and galvanized international support. Although Western support often rallied around human rights in Tibet, the right to self-determination is understood to be an important fundamental right. This applied to Tibetans as well since by many accounts they had been independent when invaded. Freedom still means independence to Tibetans as well as many of their Western supporters. Even as the Dalai Lama started in 1996 to explain in more detail to Tibetans his ambiguous meaning of a “middle way” navigating between Chinese control and independence in the concept of “greater autonomy,” freedom continues to be the central issue for Tibetans. The Tibetan freedom movement gained worldwide support of unprecedented proportions in the nineties and it is highly unlikely that for those people freedom means a Kosovo style autonomy for Tibet within China.

More than a million people have given their lives for Tibet’s freedom, untold have been tortured, displaced, suffered from near starvation, degraded, discriminated against, humiliated, traumatized. When the Dalai Lama says in 1996, “our definition of freedom is not independence,” it is difficult to imagine what Tibetans feel.

Even though the Dalai Lama had spoken of autonomy already since 1988, to most Tibetans it meant independence, although deferred. From 1995 onward, however, the Dalai Lama and his spokespeople began to say in English language publications that he had decided to work within a Chinese framework — i.e. freedom means autonomy, not independence — already in 1973! This piece of information started to be circulated seriously among the Tibetan people only as recently as 1997, when it was brought up in the Assembly prior to the Dalai Lama’s visit to Taiwan. It seems not yet to have completely penetrated the collective Tibetan psyche, but where it has, it was felt to complete the betrayal of the Tibetan dream.

Religious commitment or political allegiance?

The oracles’ “prophesies” mentioned “cause of Tibet” in tandem with the “health and life of the Dalai Lama,” or his well-being. To most Tibetans they are so closely related to mean almost the same thing. “We will be independent one day,” a woman tells the Associated Press March 10th 1999, on the fortieth anniversary of the Tibetan national uprising, “as long as the Dalai Lama is alive, we have hope.” This statement sums up the sentiments of most Tibetans, especially among the still very high percentage of illiterate ones. In that fundamentalist fusion of the cause of Tibet and life of Dalai Lama resonates at the same time what has been lost and the desperate need to preserve whatever is left: the institution of Dalai Lama. Thus, especially on an emotional level, the cause of Tibet has come to mean the preservation of the institution of Dalai Lama.

This might be one reason why the government demands of Tibetans to strengthen their relationship with him. As already mentioned, from a religious point of view, a master’s health will suffer as a result of a broken or defiled spiritual relationship. The Dalai Lama himself gave as a reason for prohibiting the practice of Dorje Shugden in his March 22, 1996 teaching the danger to his health. He had threatened then that if they wanted him dead, Tibetans had only to rely on Dorje Shugden. Yet, he also tells people, “My horoscope says I will live until I am more than one hundred twenty, my dreams suggest more than one hundred. I myself believe that I will live into my nineties. As I get older I find my physical health getting better, I think, because of Tibetan medicine, holistic medicine.” The Dalai Lama continues to bar those who rely on the protector, for allegedly harming his health and life, from his teachings and initiations worldwide.

The model of a religious relationship is used here in the political context, another source of confusion. While the religious relationship must be voluntary, one of free choice, the political one in the case of Tibetans is not, since the Dalai Lama is the non-elected head of state. Unlike in Tibet and in the early exile days, if a Tibetan today (since the mid-90s) does not attend the Dalai Lama’s teachings or a monk is ordained by abbots or other high monastic dignitaries, as was common in the more than two thousand year old Buddhist tradition, rather than the Dalai Lama, it is assumed there is something wrong with that person. The loyalty to the Dalai Lama demanded for social and political reasons is not exactly the traditional religious relationship between Buddhist master and disciple. It is a mixture in which today the allegiance to an absolute ruler prevails.

As one Buddhist master expressed it, “It is strange, this devotion to His Holiness. It has nothing to do with the Guru devotion of the Dharma. It is something else, something totally different. It is more like a political feeling. Because of His Holiness receiving international recognition — the Nobel Peace Prize and so on — we see him as a great Tibetan hero, a great leader. Religious devotion is now all mixed up with this nationalistic and political feeling for someone like our king. This mixture finally produces something very strange in the mind: a dedication to someone for whom one is ready to criticize and give up everything else, including the Buddha.”

As His Holiness stated on many occasions, he plans to live a hundred years — at least into his eighties. If his health and life were so fragile that “a few people,” as the exile government describes the numbers of those who rely on Dorje Shugden, breaking religious commitments with the Dalai Lama could endanger his life, how could it be strong enough at the same time to absorb all the many tens and even hundreds of thousand commitments he asked others to break? He stated early on, in his March 1996 teachings, that people should not worry about breaking their commitments to Dorje Shugden, which is first and foremost a commitment to their Guru and Tsong Khapa’s lam.rim teachings, that he, the Dalai Lama, would take care of it.

The Buddhist explanation of cause and effect would preclude such individual powers. Each person ultimately has to face the consequences of his or her own actions and broken commitments without fail. This the Buddha taught. It is highly unlikely that the Dalai Lama would demonstrate so unequivocally that he does not believe in karma.

Perhaps, it is a question of spiritual authority: who has more power, the Dalai Lama or the other masters to whom he and Tibetans are bound by vows? Whoever is spiritually more powerful can absorb the negativities of the others breaking their vows. Or the good karma of abiding by the vows of the more powerful Guru will override the negative karma of breaking vows with the less powerful.

This strange un-Buddhist sounding equation is one possible explanation people are left with in contemplating the existential dilemma the Dalai Lama’s “advice” has presented for them. He has not given any other “advice” besides to stop, because allegedly Dorje Shugden harms. No dialogue, no discussion, no reasonable explanation. If on the other hand he were to mean that those who rely on Dorje Shugden do not have virtue, because a commitment to evil cannot make virtue and, as he said in Germany, they are evil like the Nazis, then he would also have to admit that his own heritage is contaminated with this evil. He, too, at one time worshiped this evil spirit as did both his main mentors, Kyabje Ling and Trijang Rinpoches, and almost all of his other Gelugpa mentors from whom he received extensive teachings and vows up till the late 1970′s. It would mean that because they were all listening to this evil spirit, the whole Gelugpa transmission lineages that came out of Tibet are contaminated with evil and hence null and void which could be seen as a reason for founding a new Buddhist tradition.

However, those who rely on Dorje Shugden as a valid protector see their commitment first and foremost to the Buddha as embodied by their spiritual master and the Buddha’s teachings as preserved in Tsong Khapa’s tradition. This is simply the way relying on protectors works for any of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions.

The protector is part of a tradition he or she protects, a tradition embodied by a master believed to be the door to all Buddhist understanding and accomplishments. There is no way a Buddhist can rely on an evil spirit through a legitimate master and the authentic teachings of the Buddha. Tsong Khapa’s way of having ordered the stages of the path to enlightenment were, at least in Tibet, considered by all of the major Buddhist traditions to embody authentic teachings of the Buddha. Each tradition necessarily has its own perspective of the Buddha’s teachings.

Ironically, it is the Tibetan exile government that sees the cause of Tibet “to rely on pure protectors,” as they taught the children in schools in 1996 and demanding political allegiance replace a spiritual bond. The spiritual relationship between master and disciple is necessarily based on choice and freedom. It is used here as a front for the relationship between an unelected political leader and his followers. If the Dalai Lama ran for office today, he would win. Everyone assumes this and it is, no doubt, true. But this is not the point here. The Charter contains a clause that it cannot be changed. As I understand it, although the charter can be amended, it cannot be abandoned or the fundamental structure changed. Thus the Dalai Lama is non-elected head of the government for the duration of life in exile. After Tibetans go back to Tibet, he has said he will give up political power. Given the political realities, one could say that this is not a big sacrifice now.

Sectarianism

The cause of Tibet and the institution of Dalai Lama seem to have become so identified in the minds of Tibetans as to become their sole national identity in diaspora. The Tibetan people believe that the Tibetan cause is independence for Tibet. Thus it is difficult to perceive the Dalai Lama as anything else but a symbol of Tibetan freedom, and, no matter what the linguistic acrobatics attempting to prove the contrary, the Dalai Lama is still a symbol of Tibetan freedom for the rest of the world as well.

To the Dalai Lama, on the other hand, the “cause of Tibet” seems to mean something else. It means Tibetan “unity.” As pointed out earlier, to Western people the Dalai Lama gives as one of the main reasons for his prohibition of the protector that he is sectarian and that he endangers Tibetan unity. To the Dalai Lama, Tibetan unity seems to mean non-sectarianism understood as a positive entity, a world view, rather than the absence of conflict. This, as everything else, is complicated by the mixture of religion and politics. The non-sectarian unity the Dalai Lama is promoting, understood as a modern synthesis between religion and politics, would necessarily secularize and hence destroy religion on the one hand and result in abolishing political opposition on the other.

Separating them, would diminish the Ganden Potang government’s political authority and transform it into a power that would require at least a formal endorsement of force, even if limited by circumstances to use it. This however would be difficult to reconcile with the Dalai Lama’s uncompromising commitment to non-violence. Hence, the basis has to be found in religion. I would like to trace the components of this new “non-sectarian religion” that is turning almost unopposed into a kind of Mahayana fundamentalism.

As already mentioned, chos.lugs ri.med is translated not only with non-sectarianism or ecumenism but also with secular ethics, which is clearly misleading in the Tibetan context, since the administrative structure established in 1991 expressly states the government to be both religious and political as exemplified by the Dalai Lama. It precludes secularism altogether. Had the Dalai Lama been really committed to a secular government, he had his chance to use his overwhelming influence in 1991 to establish one and separate religion from politics. He chose not to.

Clearly, it would have diminished his influence the majority of Tibetans feel is so important at this difficult historical juncture. Perhaps Samdong Rinpoche expresses the religious basis of the exile government’s charter most clearly, “Our [government's] policies are based on religious mind or on the basic principle of religion and that does not mean it is Buddhism or Hinduism or any -ism. We say the eternal Dharma. The eternal Dharma subscribes to truth, non-violence and equality. And this has been the essence of eternal Dharma; Dharma and polity become one and the religious mind is governing the provisions of our polity.”

This is clearly not a government by the people for the people, since most of them could not discern properly when politics uses religion and vice versa. Leadership for that type of system would have to be left up to the vision and insights of the enlightened masters as practiced in Tibet for the last four hundred years. The equivocation built into “cause of Tibet” that confuses so many people means to the Tibetan people the political cause of independence and to the Dalai Lama a new ground of non-sectarian pseudo-religious unity — perhaps a global Buddhism.

The equivocation mirrors the inevitable split between religion and politics in the modern world that the Dalai Lama and his circle desperately try to keep together for the sake of the Tibetan people. It is thus not “unity” understood as secularism but a “non-sectarianism” with its historical precedent in Tibet that seems to be the heart of the meaning of “Tibetan cause” for the Dalai Lama, especially in the context of the Dorje Shugden conflict. Unity here is first religious non-sectarianism and, according to the Dalai Lama, “non-sectarian [among the Tibetan Buddhist traditions Sakya, Nyingma, Kagyu, Gelug] means not only to respect but to practice [them] simultaneously.”

As I understand non-sectarianism, it is the absence of conflict and respect for each other’s right to differ. The freedom to do so can best be guaranteed by a secular state whose legal authority is committed to enforce the law guaranteeing basic rights. It cannot be guaranteed by another religion synthesizing all existing traditions, because that would preclude the freedom of each to choose whether or not it wanted to be synthesized. In a secular state that guarantees religious freedom there would be room for all, the different traditions as well as a fusion, just as today we can still enjoy Mozart or Dufay played on traditional instruments as well as fusion, jazz, pop, whatever. There is room enough for all. It is not necessary to destroy the past to forge a new synthesis. It evolves naturally. This is one important lesson freedom understood as liberty has taught. In the Tibetan context, unless religion and politics can be separated, that freedom will not become a genuine experience.

When I asked the Dalai Lama in December 1997 with which of his many accomplishments he is most pleased, he mentioned the contribution he made to “the unity among the four Tibetan traditions, you know Nyingma, Kagyu, Gelug, Sakya,” which clearly he sees this to be his life’s work. From the point of view of eternal Dharma, all religions and Buddhist traditions are equal. His Holiness is truly committed to making equal all religious traditions especially in his Tibetan sphere of influence where now Bön, a non-Buddhist set of beliefs, is seen to be equal to the various Tibetan Buddhist traditions such that it has served as preliminary instruction to the Kalachakra initiation (New York 1991).

Surely, in this context, today, Shakyamuni Buddha would be branded sectarian as well as the many highly revered scholar sages of India, like Aryadeva, etc., all of whom defeated non-Buddhists in debate under the provision that whoever lost had to take on the religious persuasion of the victor. Milarepa in eleventh century Tibet became famous for his fight with the non-Buddhists for dominance of the Mount Kailash area with lake Manasarovar — a millennia-old holy place for Hindus, Bonpos, and Buddhists alike. In addition, the most widely accepted Buddhist practices, like taking refuge in the Three Jewels, for example, could be interpreted as sectarian under the generalized “new age” form of Buddhism now taught, since traditionally it involves a commitment not to take refuge in anyone but the Three Jewels; the Buddha, Dharma and the Sangha. I am not criticizing non-sectarianism which most people understand to mean a mutual respect of each other’s difference and non-interference. I believe that such a non-sectarian approach to religion — and not the mix of religion, politics, and business common with Tibetans in exile today — builds important bridges among people as well as mutual understanding, increasing insight into one’s own tradition.

However, I think it is not necessary to destroy individual transmission lineages to accomplish this and no new synthesis based purely on Buddhist principles, rather than social-political ones, should find it necessary to do so. Buddhists traditionally believe that discriminatory views of all sorts, including religious sectarianism, prevent higher realizations. Non-sectarianism is already part of traditional Buddhism. While it must be encouraged and protected, it does not have to be newly invented and imposed through political means.

There are irreconcilable contradictions built into non-sectarianism understood as a positive entity — as the Dalai Lama does with his emphasis on practicing all simultaneously — since anyone who does not agree with its doctrine as the dominant view even for even good reasons would be considered sectarian. The extremist idea that all those who are forced into a group by virtue of arbitrarily declaring a deity in its pantheon evil are therefore evil and do not have any rights, as the Dalai Lama suggested in Germany, sets a dangerous precedent, something not lost on Nyingma and Kagyu practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism.

If one looks at possible motives for the Dalai Lama to have develop this unusual doctrine and what are his aims in promoting it so strongly, the first thing that comes to mind is historical sectarianism.

In Tibet it was kept mostly under control in recent history and in exile during the early days when the exile government did not yet exert the tight control it does now, the old wounds broke out into the open. Perhaps the noise was just the clamor of freedom and nothing that could not have been fixed with open debates, teaching and learning the tolerance the Dalai Lama proclaims worldwide to be the prerogative of Tibetan Buddhism. But free speech was not encouraged. The wounds festered. Surely, some of this must have motivated His Holiness to develop his non-sectarian approach which seems more like an ethical humanism he says he considers almost like a religion with great spiritual resources.

Instead of developing fora for discussion, control over thought and speech increased in exile using the ubiquitous threat from the Chinese as an instrument to curtail any creative solutions to the many complex problems. The Dalai Lama’s attempts of secularizing Tibetan Buddhism displaced the religiosity into the political domain where the conservative element is getting ever stronger in its control over correct religious views including protectors. “People and deities are exactly the same. There are official deities and unofficial ones. Only the deities recognized by the government are allowed to be revered. To revere unofficial deities is against the law.”

A step back into history might be required here to find out more about why the Dalai Lama is trying to fix something that many people believe is not broken or not the most urgent problem in need of attention. Many Tibetans do not think of themselves as sectarian, be that Gelug, Sakya, Kagyu, Nyingma. There has been a lot of productive interaction between them, both in Tibet and in exile, and even though the potential of sectarian conflicts is there, they have not been the dominant problem in the exile community. The dominant one is the political status of Tibet, as it would be for any group in exile, and in this proximity of Tibetan independence and sectarianism lies the origin of the Dorje Shugden conflict.

The Dalai Lama, immediately after telling me that he is most pleased with his contribution to Tibetan “unity,” goes on to say, “To some people, this is a lot of noise (laughs), especially like Shugden…” And again, after he explains that non-sectarian means to practice the different traditions simultaneously, he tells me that Dorje Shugden, “…this spirit is an obstacle to this promotion [of non-sectarianism].” The reason, this protector is mostly practiced by Gelugpas and, he explains, “the worship of this spirit means you should not touch Nyingma tradition.”

I remembered how deeply disturbed I was when reading in the sensationalist Newsweek article that first publicized the Dorje Shugden conflict worldwide, “Above all, the Shugdens are angry that the Dalai Lama is promoting dialogue between the Yellow Hats and another major branch of Tibetan Buddhism, Nyingma, or the Red Hats. The Shugdens consider it a sin even to talk to Red Hats, or to touch Nyingma religious works.” Of all the lies that were spread through the media, this was most troubling to me because I knew it first hand to be a lie. I had been to Gelugpa monasteries in India that rely on Dorje Shugden with a long tradition of yearly rituals for Padmasambhava performed with Nyingma texts.

In fact, many Gelugpa monasteries or temples I have seen, where Dorje Shugden is one of the protective deities, prominently display Padmasambhava statues, something denied by those driving the war of words. These statues have been there for a long time and were never removed. They are still there. I have seen the Nyingma collected works in the residences of Gelugpa Lamas who were known to rely on Dorje Shugden, and I photocopied Nyingma texts for the use of one of them. Here it was again, this time the Dalai Lama himself telling me that “once you touch Nyingma tradition, even one text of Nyingma, in your house, your room, this spirit will destroy you.” I know this to be untrue.

The Nyingma-Gelug differences are doctrinal just like the difference between Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhism. This does not mean they have to fight each other or denounce one another as sectarian. To exploit doctrinal differences for sectarian ends is unskillful and unacceptable and to impute sectarianism onto doctrinal differences is looking at the problem only from one side. Moreover, charges of sectarianism close off any kind of rational debate and stir up religious sentiments better left alone.