Overview

Dorje Shugden (Wylie: rdo-rje shugs-ldan), “Powerful thunderbolt”; also known as Dhol-rgyal) is a relatively recent, but very controversial, deity within the complex pantheons of Himalayan Buddhism. There exist different accounts and claims on Dorje Shugden’s origin, nature and function.

Origin, Nature and Functions

According to researcher Kay: “Whilst there is a consensus that this protector practice originated in the seventeenth century, there is much disagreement about the nature and status of Dorje Shugden, the events that led to his appearance onto the religious landscape of Tibet, and the subsequent development of his cult.” [2]

There are two dominant views: [3]

One view holds that Dorje Shugden is a ‘jig rten las ‘das pa’i srung ma (an enlightened being). Opposing this Position is a view which holds that Dorje Shugden is actually a ‘jig nen pa’i srung ma (a worldly protector).

Kay examines: [3]

“One view holds that Dorje Shugden is a ‘jig rten las ‘das pa’i srung ma (an enlightened being) and that, whilst not being bound by history, he assumed a series of human incarnations before manifesting himself as a Dharma protector during the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama. According to this view, the Fifth Dalai Lama initially mistook Dorje Shugden for a harmful and vengeful spirit of a tulku of Drepung monastery called Dragpa Gyaltsen, who had been murdered by the Tibetan government because of the threat posed by his widespread popularity and influence. After a number of failed attempts to subdue this worldly spirit by enlisting the help of a high-ranking Nyingma lama, the Great Fifth realised that Dorje Shugden was in reality an enlightened being and began henceforth to praise him as a Buddha. Proponents of this view maintain that the deity has been worshipped as a Buddha ever since, and that he is now the chief guardian deity of the Gelug Tradition. These proponents claim, furthermore, that the Sakya tradition also recognises and worships Dorje Shugden as an enlightened being. The main representative of this view in recent years has been Geshe Kelsang Gyatso who, like many other popular Gelug lamas stands firmly within the lineage tradition of the highly influential Phabongkha Rinpoche and his disciple Trijang Rinpoche.” [4]

And

“Opposing this Position is a view which holds that Dorje Shugden is actually a ‘jig nen pa’i srung ma (a worldly protector) whose relatively short lifespan of only a few centuries and inauspicious circumstances of origin make him a highly inappropriate object of such exalted veneration and refuge. This view agrees with the former that Dorje Shugden entered the Tibetan religious landscape following the death of Tulku Dragpa Gyaltsen, a rival to the Great Fifth and his government. According to this view, however, the deity initially came into existence as a demonic and vengeance-seeking spirit, causing many calamities and disasters for his former enemies before being pacified and reconciled to the Gelug school as a protector of its teachings and interests. Supporters of this view reject the pretensions made by devotees of Dorje Shugden, with respect to his Status and importance, as recent innovations probably originating during the time of Phabongkha Rinpoche and reflecting his particularly exclusive and sectarian agenda. The present Dalai Lama is the main proponent of this position and he is widely supported in it by representatives of the Gelug and non-Gelug traditions.” [5]

Regarding English scholarly discussions, Kay states: “Scholarly discussions of the various legends behind the emergence of the Dorje Shugden cult can be found in Nebesky-Wojkowitz (1956), Chime Radha Rinpoche (1981), and Mumford (1989). All of these accounts narrate the latter of the two positions, in which the deity is defined as a worldly protector. The fact that these scholars reveal no awareness of an alternative view suggests that the position which defines Dorje Shugden as an enlightened being is both a marginal viewpoint and one of recent provenance.” [6] [*1]

Although proponents of the view that Dorje Shugden is an enlightened being claim that the Sakya tradition also recognises and worships Dorje Shugden as an enlightened being [7], Sakya Trizin, the present head of the Sakya tradition, states that some Sakyas worshipped Shugden as a lower deity, but Shugden was never part of the Sakya institutions. [8] Lama Jampa Thaye, an English teacher within both the Sakya and the Kagyu traditions and founder of the Dechen Community, maintains that “The Sakyas generally have been ambivalent about Shugden [...] The usual Sakya view about Shugden is that he is controlled by a particular Mahakala, the Mahakala known as Four-Faced Mahakala. So he is a ‘jig rten pai srung ma, a worldly deity, or demon, who is no harm to the Sakya tradition because he is under the influence of this particular Mahakala.” [9]

Then there are lamas who regard Dorje Shugden as a destructive and malevolent (or demonic) force, like Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche [10], Mindrolling Trichen Rinpoche [11], former head of the Nyingma school, and Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche. The latter is head of 25 monasteries in Bhutan and holds the view: People who practice Shugden “will get a lot of money, a lot of disciples, and a lot of problems.” [12]

According to Nebesky-Wojkowitz, lower class deities, known as the ‘jig rten las ‘das pa’i srung ma, are mundane or worldly deities who are still residing within the spheres inhabited by animated beings and taking an active part in the religious life of Tibet, most of them by assuming from time to time possession of mediums who act then as their mouthpieces. [13]

The view that Dorje Shugden may be a worldly protector can be indicated by the fact that Shugden is invoked by oracles. One of these oracles is Kuten Lama, an uncle of Kelsang Gyatso, who has served as an oracle of Dorje Shugden for more than 20 years, for both monastic and lay Buddhists who sought divine assistance. [14]

[Editor’s note: Enlightened protectors can manifest in worldly form in order to be more accessible to us.]

Origins

The historical origin of Dorje Shugden is unclear. Most scriptural documents on him appeared at the 19th century. There exist different orally transmitted versions of his origins, but in the key points they contradict one another. Some references to Shugden are found in the biography of the 5th Dalai Lama, so there is some agreement that the origins of Shugden stem from that time. However, the claim of Shugden followers that the 5th Dalai Lama wrote a praise on Dorje Shugden lacks historical evidence, according to researcher von Brück: there is no historical record of such a praise neither in the biography of the 5th Dalai Lama nor elsewhere.[110] Pabongkha Rinpoche, a Gelug Lama of the 20th century, who received this practice from his root guru, is attributed with spreading reliance on Dorje Shugden widely within the Gelug tradition “during the 1930s and 1940s, and in this way a formerly marginal practice became a central element of the Gelug tradition.” [15]

This issue has a long history and involves not only the Fourteenth Dalai Lama but also the Thirteenth and the Fifth Dalai Lamas. There is an extensive essay on its origin and history in The Shuk-Den Affair: Origins of a Controversy [16] by Prof. George Dreyfus.

According to Mills, Shugden is “supposedly the spirit of a murdered Gelukpa lama who had opposed the Fifth Dalai Lama both in debate and in politics. Shugden is said to have laid waste to Central Tibet until, according to one account, his power forced the Tibetan Government of the Fifth Dalai Lama to seek reconciliation, and accept him as one of the protector deities (Tib. choskyong) of the Gelukpa order.” [17]

According to Dreyfus “When asked to explain the origin of the practice of Dorje Shukden, his followers point to a rather obscure and bloody episode of Tibetan history, the premature death of Truku Drakba Gyeltsen (sprul sku grags pa rgyal mtshan, 1618-1655). ”Drak-ba Gyel-tsen” was an important Gelug lama who was a rival of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngak-wang Lo-sang Gya-tso (ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1617-1682). [16] He suggests, “that the events surrounding Drak-ba Gyel-tsen’s death must be understood in relation to its historical context, the political events surrounding the emergence of the Dalai Lama institution as a centralizing power during the second half of the seventeenth century. The rule of this monarch seems to have been particularly resented by some elements in the Geluk tradition. It is quite probable that Drak-ba Gyel-tsen was seen after his death as a victim of the Dalai Lama’s power and hence became a symbol of opposition.” [16]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, rituals related to Dorje Shugden began to be written by prominent Gelug masters. The Fifth On-rGyal-Sras Rinpoche (1743-1811, skal bzang thub bstan ‘jigs med rgya mtsho), an important Lama and a tutor (yongs ‘dzin) to the 9th Dalai Lama wrote a torma offering ritual[18]. Also, the Fourth Jetsun Dampa (1775 – 1813, blo bzang thub bstan dbang phyug ‘jigs med rgya mtsho), the head of Gelug sect in Mongolia also wrote a torma offering to Shugden in the context of Shambhala and Kalachakra. [19]

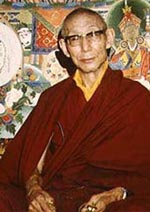

Key figures in the modern popularization of worshipping Dorje Shugden are Je Pabongkha (1878-1944), a charismatic Khampa lama who seems to have been the first historical Gelugpa figure to promote Shugden worship as a major element of Gelugpa practice; and Trijang Rinpoche (1901-1981), a Ganden lama who was one of the tutors of the present Dalai Lama. Pabongkha Rinpoche put great emphasis on spreading this practice and thus made the practice quite popular in the Gelug tradition. The Life-Entrusting (Sogde) practice was seen by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama as going against the Buddhist principles of refuge (Triratna), therefore he scolded Pabongkha Rinpoche for it. Pabongkha Rinpoche stated in a letter to the 13th Dalai Lama, that this is actually his fault. He excused himself for having acted against the triratna-pledges and for having provoked the wrath of Nechung, explaining that the deity (lha) Shugden played a special role at the time of his birth, and he promised to stop worshipping Shugden and to avoid performing the rituals regarding that deity. [109] However, after the death of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, he began to spread the practice even more than previously.

In the beginning, Dorje Shugden was seen by Pabongkha Rinpoche as a worldly deity who has to be controlled by tantric power [108], it is not clear when and how the view that he is an emanation of Manjushri appeared. According to Lama Pabongkha’s view, Drakpa Gyeltsen was an incarnation of Dorje Shugden but his death is not the cause of Dorje Shugden. He established a line of arguments arguing that Shugden has a very close connection to practitioners of Je Tsongkhapa’s tradition and is now their powerful protector and able to bestow blessings and create appropriate conditions for Dharma realisations to flourish. To do this, he established the idea that the original three protectors of Je Tsongkhapa’s tradition (Kalarupa, who was bound by Tsongkhapa himself, Vaisravana and Mahakala) have gone to their pure lands and have no power anymore because the Karma of the Gelug adepts has changed and they should now follow Shugden.

Dreyfus wrote in his essay “The Shugden Affair”: [20]

“Pabongkha suggests that he is the protector of the Gelug tradition, replacing the protectors appointed by Tsongkhapa himself. This impression is confirmed by one of the stories that Shugden’s partisans use to justify their claim. According to this story, the Dharma-king has left this world to retire in the pure land of Tushita having entrusted the protection of the Gelug tradition to Shugden. Thus, Shugden has become the main Gelug protector.”

“Though Pabongkha was not particularly important by rank, he exercised a considerable influence through his very popular public teachings and his charismatic personality. Elder monks often mention the enchanting quality of his voice and the transformative power of his teachings. Pabongkha was also well served by his disciples, particularly the very gifted and versatile Trijang Rinpoche (khri byang rin po che, 1901-1983), a charismatic figure in his own right who became the present Dalai Lama’s tutor and exercised considerable influence over the Lhasa higher classes and the monastic elites of the three main Gelug monasteries around Lhasa. Another influential disciple was Tob-den La-ma (rtogs ldan bla ma), a stridently Gelug lama very active in disseminating Pabongkha’s teachings in Kham. Because of his own charisma and the qualities and influence of his disciples, Pabongkha had an enormous influence on the Gelug tradition that cannot be ignored in explaining the present conflict. He created a new understanding of the Gelug tradition focused on three elements: Vajrayogini as the main meditational deity (yi dam), Shugden as the protector, and Pabongkha as the guru.”

“Where Pabongkha was innovative was in making formerly secondary teachings widespread and central to the Gelug tradition and claiming that they represented the essence of Tsongkhapa’s teaching. This pattern, which is typical of a revival movement, also holds true for Pabongkha’s wide diffusion, particularly at the end of his life, of the practice of Dorje Shugden as the central protector of the Gelug tradition. Whereas previously Shugden seems to have been a relatively minor protector in the Gelug tradition, Pabongkha made him into one of the main protectors of the tradition. In this way, he founded a new and distinct way of conceiving the teachings of the Gelug tradition that is central to the Shugden Affair.”

The conflict and refutations cannot be understood fully without seeing the complex historical, religious, social, scientific, and cultural background and the struggle of the reformers, conservatives, and traditionalists in Tibet. The practice of Shugden involves family relations too. On the other hand, Tibet was quite isolated, and there was not much modern scientific outlook. Even at the time when the Chinese took over Tibet, Buddhist teachers in Tibet taught (and this was also taught to HH the Dalai Lama) that the earth was flat, that the moon shone from itself and was the same distance from the Earth as the sun is, and the texts on the “history” of Tibet told about building a thousand stupas in one day, and the like.

The dispute itself

“The Shugden dispute represents a battleground of Views on what is meant by religious and cultural freedom. [21]”

According to researcher Mills: “The object of the controversy – the deity Dorje Shugden, also named Dholgyal by opponents of its worship – had been a point of controversy between the various orders of Tibetan Buddhism since its emergence onto the Tibetan scene in the late seventeenth Century, and was strongly associated with the interests of the ruling Gelukpa Order.” [22]

Mills continues: “[..] the deity retained a controversial quality, being seen as strongly sectarian in character, especially against the ancient Nyingmapa school of Tibetan Buddhism: the deity was seen as wreaking supernatural vengeance upon any Gelukpa monk or nun who ‘polluted’ his or her religious practice with that of other schools. Most particularly those of the Nyingmapa. This placed the deity’s worship at odds with the role of the Dalai Lama, who not only headed the Gelugpa order but, as head of State, maintained strong ritual relationships with the other schools of Buddhism in Tibet, particularly the Nyingmapa. The deity thus became the symbolic focus of power struggles, both within the Gelukpa order and between it and other Buddhist schools.” [23]

Driving this dispute is the inherent nature of Dorje Shugden, which is to “protect” the Gelug lineage from adulteration by the traditions of other lineages, especially the Nyingmapa. His practice includes a promise not even to touch a Nyingma scripture, and several pro-Shugden lamas have said Shugden will kill those who violate this vow. [Editor’s note: there is no evidence of this “promise” in Dorje Shugden’s practice nor of this statement from ‘pro-Shugden lamas’.]

“Conservative” Gelugpas may find such language congenial to their views, while “liberals” are more likely to stress the arbitrary nature of such sectarian divisions. The dispute appears mainly theological; however the extent to which theology dovetails with more secular interests of particular monasteries, families, and other power-holders should not be overlooked.

Though the roots of the Dorje Shugden controversy are more than 360 years old, the issue surfaced within the Tibetan exile community during the 1970s [24] after Zemey Rinpoche published the Yellow Book, which included stories – passed by Pabongkha Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche – about members of the Gelugpa sect who practiced Gelug and Nyingma teachings together and were killed by Shugden. According to Mills: “in defence of the deity’s efficacy as a protector, [this book] named 23 government officials and high lamas that had been assassinated using the deity’s powers.” [25]

According to Mumford: Dorje Shugden is “extremely popular, but held in awe and feared among Tibetans because he is highly punitive.” [26]

After the publication of the Yellow Book, the current (fourteenth) Dalai Lama expressed his opinion in several closed teachings that the practice should be stopped, although he made no general public statement. According to Mills: “In 1978, His Holiness spoke out publicly against the use of the deity as an institutional protector, although maintaining that individual should decide for themselves in terms of private practice. It was not until Spring 1996 that the Dalai Lama decided to move more forcefully on the issue. Responding to growing pressure – particularly from other schools of Tibetan Buddhism such as the Nyingmapa, who threatened withdrawal of their support in the Exiled Government project – he announced during a Buddhist tantric initiation that Shugden was ‘an evil spirit’ whose actions were detrimental to the ’cause of Tibet’, and that henceforth he would not by giving tantric initiation to worshippers of the deity (who should therefore stay away), since the unbridgeable divergence of their respective positions would inevitably undermine the sacred guru—Student relationship, and thus compromize his role as a teacher (and by extension his health).” [27]

Once a marginal practice [28], the worship of Dorje Shugden became, under Pabongkha Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche, a widespread practice in the Gelug school, and many Gelug lamas practised it and spread the worship of Dorje Shugden. According to the XIVth Dalai Lama, the practice became so widespread that only very few, like Gen Pema Gyaltsen (the ex-abbot of Drepung Loseling monastery) opposed it: “For some time he was the only one – a lone voice against the worship. Even I was involved in the propitiation at the time. Ling Rinpoche did go through the motions, but in reality, his involvement was reluctant. As far as Trijang Rinpoche was concerned, it was a special, personal practice and Zong Rinpoche was similarly involved.” [29]

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama holds the view “This is not an authentic tradition, but a mistaken one. It is leading people astray. As Buddhists, who take ultimate refuge in the three jewels, we are not permitted to take refuge in worldly deities.” [30]

Therefore he advised against the practice although he has in the past received Shugden empowerments from one of his teachers, Trijang Rinpoche, and practised it. That he gave up one of the practices he received from one of his teachers has provoked the criticism of NKT members and Shugden adherents (who strongly emphasize Guru obedience). They argued that he has failed to observe the vows given by one of his teachers and has “broken with his Guru” and that he has forced others to do likewise. [107]

The Dalai Lama opposes that view and cites many examples of Buddhist history which show that there are many lineage masters who disagreed with or corrected their own teacher’s false assertions or views, after giving evidences he concludes “Even if something is or was performed by great spiritual teachers of the past, if it goes against the general spirit of the teachings, it should be discarded.” [31]

Further he stresses the importance that people should not follow his advice blindly but instead they should thoroughly investigate; “Others of you may be thinking, “well I am not sure of the reasons, but as it is something that the Dalai Lama has instructed, I must abide by it”. I want to stress again that I do not support this attitude at all. This is a ridiculous approach. This is a position that one should come to by weighing the evidence and then using one’s discernment about what it would be best to adopt and what best to avoid.” [32]

In an interview, Alexander Berzin pointed out as the central elements of the present conflict: There are commitments on the levels of friendship, allegiance, loyalty, and bondings, both from student to teacher as well as from the student to their group. These life-long commitments are established through tantric empowerments. With respect to this there is, according to Berzin, a significant difference between Shugden followers and (almost) all other Tibetan Buddhists: followers of the ‘Shugden cult’, who receive the initiation, are told that this ‘protector’ or this ‘practice’ may never be given up again. However, according to an old instruction of the master Ashvaghosha, it’s the case that one may end the teacher-student-relationship even when having received an empowerment. There can be different reasons for ending such a relationship: if one has failed to sufficiently investigate one’s teacher beforehand or if one has critically distanced oneself to him and his methods. It’s said, that one may then respectfully distance oneself from such a teacher but that one should avoid speaking harsh words about him and his practice. [33]

Today’s Controversy

Today’s controversy surrounding the deity refers to a particular brand of Gelugpa exclusivism that emerged in Central and Eastern Tibet during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where the deity was considered to demarcate the boundaries of Gelugpa religious practice, especially in opposition to growing influence of Ri-me, literally “non-sectarian”. Many Gelugpas, as well as many Kagyupas, Sakyapas and Nyingmapas, began to follow the ideas of the Ri-me movement, but conservative Gelugpas, especially Pabongkha Rinpoche, became concerned over the “purity” of the Gelug school and opposed the ideas of Ri-me. Pabongkha Rinpoche established instead a special Gelug exclusivism. [34] Different sources state that disciples of Pabongkha Rinpoche destroyed Nyingma monasteries or converted them to Gelug monasteries and destroyed statues of Padmasambhava. [35]

[Editor’s note: This claim of Pabongkha Rinpoche being sectarian is not substantiated. Please see http://shugdensociety.wordpress.com/2009/11/14/defamation-of-je-phabongkhapa/ for a more balanced view of the situation.]

This on-going tension has reached new heights in the Tibetan exile context, where the Fourteenth Dalai Lama started first to distance himself from Shugden and later used his position as the political and religious head of Tibet to stop the growing influence of the worship of Shugden by advising against it. [36]

The dispute developed international dimensions in the 1990s, when the Dalai Lama’s statements against the practice of Shugden challenged the British-based New Kadampa Tradition to oppose him. Geshe Kelsang said that Tibetan practitioners of Dorje Shugden asked him to help them. As a result, Kelsang Gyatso sent a public letter [37] to the Dalai Lama, to which he did not receive any response, and subsequently created the Shugden Supporter Community (SSC), which organised protests and a huge media campaign during the Dalai Lama’s teaching tour of Europe and America, accusing him of religious persecution and opposing the human rights to freedom of religious practice and of spreading untruths. According to Tashi Wangdi, Representative to the Americas of the Dalai Lama, there was no suppression of Shugden worship. “Officially there has never been any repression or denial of rights to practitioners,” said Wangdi. “But after His Holiness’ advice [against worship] many monastic orders adopted rules and regulations that would not accept practitioners of Shugden worship in their monastic order.” [38]

(see The Conflict in the West)

In India, some protests and opposition were organised by the Dorje Shugden Religious and Charitable Society with the support of SSC. [39]

The SSC tried to obtain a statement from Amnesty International (AI) that the Tibetan Government in Exile (specifically the 14th Dalai Lama) had violated human rights. However, AI replied in an official press release:

None of the material AI has received contains evidence of abuses which fall within AI’s mandate for action – such as grave violations of fundamental human rights including torture, the death penalty, extra-judicial executions, arbitrary detention or imprisonment, or unfair trials. [40]

This neither asserts nor denies the validity of the allegations against the CTA (Central Tibetan Administration), nor finds either side culpable. Amnesty International regards “spiritual issues” and state affairs as separate, whilst seeing the command-based nation-state as the fundamental framework for understanding the category of “actionable human rights abuses”. Fundamental to this were linked criteria of state accountability and the exercise of state force, neither of which could clearly be identified within the CTA context. [41]

At the peak of the conflict, in February 1997, three Tibetan Buddhist monks, opponents of the Shugden practice, including the Dalai Lama’s close friend and confidant, seventy-year-old Lobsang Gyatso (the principal of the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics), were brutally murdered in Dharamsala, India, the Tibetan capital in exile. The murdered monks were repeatedly stabbed and cut up in a manner resembling a ritual exorcism. The Indian police believe the murders were carried out by monks loyal to Shugden, and that the perpetrators are now under the protection of the Chinese government. [42] The Indian police have accused Lobsang Chodak, 36, and Tenzin Chozin, 40, of stabbing Lobsang Gyatso and two of his students. [112] In 2007 Interpol has issued wanted notices for Lobsang Chodak and Tenzin Chozin. [112] According to a disciple of Geshe Lobsang Gyatso, before he was killed, Lobsang Gyatso had faced many death threats, but refused any personal security. [43] The Shugden Society in New Delhi denies any involvement in the murders or threats. [44] Kelsang Gyatso distanced himself: “Killing such a geshe and monks is very bad, it is horrible. How can Mahayana Buddhists who are always talking about compassion kill people? Impossible. There are many different possible explanations [for the murders]. There are many Shugden practitioners throughout the world, and each of them is responsible for his own actions. But definitely, we can say that these murders are very bad.” [45]

Another remarkable episode concerns the decision by the young reincarnation of Trijang Rinpoche to leave the Centre Rabten Choeling in Switzerland where he had remained for years under the guidance of his lama-tutor, Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche. In a dramatic letter and in an interview on the Tibetan radio station in Dharamsala, Trijang Chogtrul Rinpoche announced his abandonment of his monastic robes in order to become ‘an ordinary person’. “Shocked by a series of still murky events, the gravest of which was the attempted murder of his former personal assistant by members of the cult, the young Trijang explained he had no intention of becoming a banner or symbol of the pro-Shugden movement.” [10]

Recent Developments

On 22 April 2008, the newly-founded Western Shugden Society – behind which is mainly the New Kadampa Tradition – began a campaign against the 14th Dalai Lama, claiming he is “banning them from practising their own version of Buddhism”. The campaigns accuse him of being “a hypocrite”, who is “persecuting his own people”. [46] Since then, the protesters follow the Dalai Lama to every city to express their point of view by means of demonstrations. The protesters in Nottingham said the ban on the prayer worshipping the spirit of Dorje Shugden was “unjust”, and pictured the worship of Dorje Shugden as “a simple prayer that encourages people to develop pure minds of love, peace and compassion.” His Holiness the Dalai Lama replied in a BBC interview that he had not advocated a ban, but he had stopped the worship of the spirit because it was not Buddhist in nature, and added, people were free to protest and it was up to individuals to decide. [111]

The political dimension

According to Kay, “whilst the conservative elements of the Gelug monastic establishment have often resented the inclusive and impartial policies of the Dalai Lamas towards the revival of Tibetan Buddhist traditions, the Dalai Lama has in turn rejected exclusivism on the grounds that it encourages sectarian disunity and thereby harms the interests of the Tibetan state.” [47]

Thus the Dalai Lama has spoken out against what he saw as spiritually harmful as well as nationally damaging. Especially during Tibet’s present political circumstances, the present Dalai Lama felt the urge to speak against Dorje Shugden practice. In sum, the Dalai Lama’s main criticisms of Shugden practice is that the “practice fosters religious intolerance and harms the Tibetan cause and unity”.

There are different political interpretations of that conflict.

In the context of the Tibetan history, Kay states: “The political policies of the Dalai Lamas have also been informed by this inclusive orientation. It can be discerned, for example, in the Great Fifth’s (1617-82) leniency and tolerance towards opposing factions and traditions following the establishment of Gelug hegemony over Tibet in 1642; in the Great Thirteenth’s (1876-1933) modernist-leaning reforms, which attempted to turn Tibet into a modern state through the assimilation of foreign ideas and institutions (such as an efficient standing army and Western-style education); and in the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s promotion of egalitarian principles and attempts to ‘Maintain good relations among the various traditions of Tibetan religion in exile’ (Samuel 1993: 550). This inclusive approach has, however, repeatedly met opposition from others within the Gelug tradition whose orientation has been more exclusive. The tolerant and eclectic bent of the Fifth Dalai Lama, for example, was strongly opposed by the more conservative segment of the Gelug tradition. These ‘fanatic and vociferous Gelug churchmen’ (Smith 1970: 16) were outraged by the support he gave to Nyingma monasteries, and their ‘bigoted conviction of the truth of their own faith’ (Smith 1970: 21) led them to suppress the treatises composed by more inclusively orientated Gelug lamas who betrayed Nyingma, or other non-Gelug, influences. Similarly, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s political reforms were thwarted by the conservative element of the monastic segment, which feared that modernisation and change would erode its economic base and the religious basis of the state. His spiritually inclusive approach was also rejected by contemporaries such as Pabongkha Rinpoche (1878-1943). As with his predecessors, the current Dalai Lama’s open and ecumenical approach to religious practice and his policy of representing the interests of all Tibetans equally, irrespective of their particular traditional affiliation, have been opposed by disgruntled Gelug adherents of a more exclusive orientation. This classical inclusive/exclusive division has largely been articulated within the exiled Tibetan Buddhist community through a dispute concerning the status and nature of the protective deity Dorje Shugden.” [48]

Another view looking more at the present situation is: “it has been suggested that the Dalai Lama, in rejecting Dorje Shugden, is speaking out against a particular quasi-political factions within the Gelug tradition-in-exile who are opposed to his modern, ecumenical and democratic political vision, and who believe that the Tibetan government” [47] “should champion a fundamentalist version of Tibetan Buddhism as a state religion in which the dogmas of the Nyingmapa, Kagyupa, and Sakyapa schools are heterodox and discredited.” [49] According to this interpretation, Dorje Shugden has become a political symbol for this “religious fundamentalist party”. [47] From this point of view, the rejection of Dorje Shugden should be interpreted “not as an attempt to stamp out a religious practice he disagrees with, but as a political statement”. According to Sparham: “He has to say he opposes a religious practice in order to say clearly that he wants to guarantee to all Tibetans an equal right to religious freedom and political equality in a future Tibet.”[50]

Dreyfus argues that although the political dimension forms an important part of that dispute, it does not provide an adequate explanation for it. [47] He traces back the conflict more on the exclusive/inclusive approach and maintains that to understand the Dalai Lama’s point of view, one has to consider the complex ritual basis for the institution of the Dalai Lamas, which was developed by the Great Fifth and rests upon “an eclectic religious basis in which elements associated with the Nyingma tradition combine with an overall Gelug orientation”. [51] This involves the promotion and practices of the Nyingma school. The 5th Dalai Lama was criticized by and has been treated in a hostile manner by conservative elements of the Gelug monastic establishment for doing this and for supporting Nyingma practitioners. The same happened when the 14th Dalai Lama started to encourage devotion to Padmasambhava, central to the Nyingmas, and when he introduced Nyingma rituals at his personal Namgyal Monastery (Dharmasala, India). Whilst the 14th Dalai Lama started to encourage devotion to Padmasambhava for the purpose of unifying the Tibetans and “to protect Tibetans from danger”, [52] the “more exclusively orientated segments of the Gelug boycotted the ceremonies”, [47] and in that context the sectarian Yellow Book was published.

Other analysts argue the opposite view, that it is the Tibetan Government in Exile which seeks to create a homogeneity of belief. Wilson argues [53] that the TGIE is a theocracy which he identifies by the following features, “religious freedom is restricted because state power is marshaled in favour of a particular set of religious beliefs (and, by extension, against others), the intention being to eradicate alternative beliefs and pursue national homogeneity of belief.” [53]

According to Wilson, the pursuit of religious homogeneity has been illustrated during “The last thirty years” which have “witnessed the growing ascendancy, both in exile and within Tibet, of the Dalai Lama as either the direct root–guru of all those firmly interested in Tibetan independence (often through the numerous mass Kalachakra empowerments he has given since 1959) or, more commonly, the indirect apex of an increasingly unified pyramid of lamaic (guru-disciple) relationships, many of which transcend the sectarian divides which became entrenched within Tibetan Buddhism during the centuries following the 5th Dalai Lama’s establishment of centralized Gelugkpa rule in Central Tibet.” In this context, by criticising the practice of Shugden, the TGIE is asserting “the functional role of religion within the constitution for a sacral political life centered on the Dalai Lama and held together primarily by acts of ritualized loyalty.” [53] or as Helmut Gassner (Swiss), a former interpreter of the Dalai Lama and a Shugden follower, argues “…for most Tibetans nothing is more important than the Dalai Lama’s life; so if one is labeled an enemy of the Dalai Lama, one is branded as a traitor and therewith ‘free-for-all’ or an outlaw.” [54]

Wilson argues that “the Dalai Lama’s request that Shugden worshippers not receive the tantric initiations — the foundation of the ‘root-guru’ relationship — from him, effectively placed them outside the fold of the exiled Tibetan polity.” [53] He establishes this view by arguing that the Tibetan Government in Exile (TGIE) is a theocracy and that the Dalai Lama’s statements in Spring 1996 “during a Buddhist tantric initiation that Shugden was an “evil spirit” whose actions were detrimental to the “cause of Tibet”” reflect the Dalai Lama’s decision to “move more forcefully” in response “to growing pressure – particularly from the Nyingmapa, who threatened withdrawal of their support in the Exiled Government project”. [55]

Jane Ardley writes, [56] concerning the political dimension of the Shugden controversy. “…the Dalai Lama, as a political leader of the Tibetans, was at fault in forbidding his officials from partaking in a particular religious practice, however undesirable. However, given the two concepts (religious and political) remain interwoven in the present Tibetan perception, an issue of religious controversy was seen as threat to political unity. The Dalai Lama used his political authority to deal with what was and should have remained a purely religious issue. A secular Tibetan state would have guarded against this.” [56]

Ardley references the following directive published by the Tibetan Government in Exile to illustrate the “interwoven” nature of the politics and religion:

“In sum, the departments, their branches and subsidiaries, monasteries and their branches that are functioning under the administrative control of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile should be strictly instructed, in accordance with the rules and regulations, not to indulge in the propitiation of Shugden. We would like to clarify that if individual citizens propitiate Shugden, it will harm the common interest of Tibet, the life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and strengthen the spirits that are against the religion.” [56]

In his concluding remarks, Wilson observes that “…the debate surrounding Shugden was primarily one of differing understandings of the constitution of religious rights as an element of state life, particularly in the context of theocratic rule. As an international dispute, moreover, it crossed the increasingly debated line between theocratic Tibetan and liberal Western interpretations of the political reality of religion as category.” In particular he sees the main failing of the Shugden Supporters Campaign as arising from their erroneous assertion of “the separation of religion and state as the basis for the understanding of religious freedom and denied any legitimate functioning role to Buddhism within the constitution of that state.” [53]

Whereas Kay states “The Dalai Lama opposes the Yellow Book and Dorje Shugden propitiation because they defy his attempts to restore the ritual foundations of the Tibetan state and because they disrupt the basis of his leadership, designating him as an “enemy of Buddhism” and potential target of the deities retribution.” [47]

According to Mills:

“Tibetan Buddhist political and institutional life centres round the activities of its four principal schools – the Nyingmapa, the Kagyud, the Sakya and the Gelukpa – the last of which was politically dominant in Tibet from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries; the four schools had the Dalai Lamas as their political figure-heads.” [58]

Mills puts the struggle of the Dalai Lama, as well as those involved, into perspective, describing e.g. “Shugden was a protector deity – a choskyong – whose historical role served to bolster the symbolic distinction between the ruling Gelukpa order and the influence of other school of Buddhist institutional thought in Tibet. As a choskyong, however, the deity’s role was more than a question of personal belief: it existed as an element within the functioning structure of state law and practice. As such, the continuity of the deity’s institutional worship within the diaspora supported a State that was institutionally sectarian at a symbolic level. This consequence of continued Shugden practice was so strongly felt, for example, that during the early I990s the Nyingmapa school threatened to remove their presence from the Tibetan Assembly of People’s Deputies – they sought to secede from a State structure whose very form and functioning was antagonistic to their presence.” [59] As a part of his conclusion from investigating the issue of human rights in that dispute, Mills states: “Whilst there was clearly also a strong issue of the actual ‘facts of the case’ the debate surrounding Shugden was primarily one of different understandings of the constitution of religious rights as an element of State life, particularly in the context of theocratic rule. As an international dispute, moreover, it crossed the increasingly debated link between theoretic Tibetan and liberal Western interpretations of the political reality of religion as a category. By this, I do not mean to imply that the CTA slipped through a loophole in human rights law. Rather that it denatured relationships of religious faith to the extent to which they are merely ‘individually held beliefs’ and ‘private practices’. Western social and legal discourse may have blinded itself to the role that such relationships play in the constitution of states as communal legal entities.” [60]

The Bristol-based Buddhist specialist Paul Williams remarked in a Guardian interview on the Shugden controversy in 1996:

“The Dalai Lama is trying to modernize the Tibetans’ political vision and trying to undermine the factionalism. He has the dilemma of the liberal: do you tolerate the intolerant?” [61]

Another point of the political dimension is the involvement of the Chinese, interested to use this conflict to undermine the unity of the Tibetans and their faith towards the Dalai Lama. So for example when the official Xinhua news agency said 17 Tibetans destroyed a pair of statues at Lhasa’s Ganden Monastery on 14 March 2006 depicting the deity Dorje Shugden, the mayor of Lhasa blamed the destruction on followers of the Dalai Lama. On the other side, according to the BBC, analysts accused China of exploiting any dispute for political ends. According to the BBC “…some analysts have accused China of exploiting the apparent unrest for political gain in an effort to discredit the Dalai Lama. Tibet analyst Theirry Dodin said China had encouraged division among the Tibetans by promoting followers of the Dorje Shugden sect to key positions of authority. ‘There is a fault line in Tibetan Buddhism and its traditions itself, but it is also exploited for political purposes’…” [62]

Background of the conflict in the Gelug tradition

Historically the Gelug tradition, founded by Je Tsongkhapa, has never been a completely unified order. Internal conflicts and divisions are a part of it and are based on philosophical, political, regional, economic, and institutional interests. In the 17th century, the Gelug order became politically dominant in central Tibet. This was through the institutions of the Dalai Lamas. Although he is not the head of the Gelug school — the head is the Ganden Tripa, the abbot of Ganden Monastery — the Dalai Lama is the highest incarnate Lama of the Gelug school, comparable to the position of the Karmapa in the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Because of his responsibility as the political and religious leader of the Tibetans, the Dalai Lama’s duty is to balance the different interests and to be sensitive towards the different traditions and relationships. “It is necessary also to reflect on what the development of such a sectarian cult has meant and continues to mean for the Dalai Lama and for all the Tibetans in exile (and also for the Tibetans in occupied Tibet, for whom the repercussions of this matter are many and of more than secondary import).”[10] There were power struggles from the 14th century onwards “competing for political influence and economical support”[63] and a tendency of a strong sectarian interpretation of the Buddha’s doctrine. This sectarian attitude was encountered in the open approach of the Dalai Lamas, especially the 5th, 13th and 14th, and through the development of the Rimé movement at the end of the 19th century, which Gelug lamas also followed.

The founder of the Gelug school, Je Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), had an open, ecumenical and eclectic approach. He used to go to all the great lamas of his time from all the different Buddhist schools and received Buddhist teachings from them. But his first successor, Khedrubje (mKhas grub rje) (1385-1483) became “quite active in enforcing a stricter orthodoxy, chasting… disciples for not upholding Tsongkhapa’s pure tradition”.[63]

According to David N. Kay:

“from this time, as is the case with most religious traditions, there have been those within the Gelug who have interpreted their tradition ‘inclusively’, believing that their Gelug affiliation should in no way exclude the influence of other schools which constitute additional resources along the path of enlightenment. Others have adopted a more ‘exclusive’ approach, considering that their Gelug identity should preclude the pursuit of other paths and that the ‘purity’ of the Gelug tradition must be defended and preserved.[64]

In the past the different approaches of Pabongka Rinpoche (1878-1943) [Editor’s note: Pabongka Rinpoche passed into clear light in 1941] (‘exclusive’ religious and political approach) and the 13th Dalai Lama (1876-1933) (‘inclusive’ religious and political approach) were quite contrary. Especially at that time, the conservative Gelugpas feared modernisation and the reforms of the 13th Dalai Lama, and tried to undermine them. As a sign of that modernisation from within the Tibetan society, the Rime movement won strong influence, especially in Kham (Khams, Eastern Tibet),

“…and in response to the Rimé movement (ris med) that had originated and was flowering in that region, Pabongkha Rinpoche (a Gelug agent of the Tibetan government) and his disciples employed repressive measures against non-Gelug sects. Religious artefacts associated with Padmasambhava — who is revered as a ‘second Buddha’ by Nyingma practitioners — were destroyed, and non-Gelug, and particularly Nyingma, monasteries were forcibly converted to the Gelug position. A key element of Pabongkha Rinpoche’s outlook was the cult of the protective deity Dorje Shugden, which he married to the idea of Gelug exclusivism and employed against other traditions as well as against those within the Gelug who had eclectic tendencies.”[48]

According to Samuel, Pabongka Rinpoche, who was a “strict purist and conservative”, “adopted an attitude of sectarian intolerance” and “instituted a campaign to convert non-Gelug gompa (monasteries) in Kham to the Gelugpa school, by force where necessary.”[65] Pabongkha Rinpoche and his disciples prompted the growing influence of the Rimé movement by propagating the supremacy of the Gelug school as the only pure tradition.[66] He based his approach on a ‘unique understanding’ of the Shunyata view in the Gelug tradition.

To show the sectarian nature of the Shugden practice, Dreyfus quotes Pabongka Rinpoche from an introduction to the text of the empowerment required to propitiate Shugden:

“[This protector of the doctrine] is extremely important for holding Dzong-ka-ba’s tradition without mixing and corrupting [it] with confusions due to the great violence and the speed of the force of his actions, which fall like lightning to punish violently all those beings who have wronged the Yellow Hat Tradition, whether they are high or low. [This protector is also particularly significant with respect to the fact that] many from our own side, monks or lay people, high or low, are not content with Dzong-ka-ba’s tradition, which is like pure gold, [and] have mixed and corrupted [this tradition with] the mistaken views and practices from other schools, which are tenet systems that are reputed to be incredibly profound and amazingly fast but are [in reality] mistakes among mistakes, faulty, dangerous and misleading paths. In regard to this situation, this protector of the doctrine, this witness, manifests his own form or a variety of unbearable manifestations of terrifying and frightening wrathful and fierce appearances. Due to that, a variety of events, some of them having happened or happening, some of which have been heard or seen, seem to have taken place: some people become unhinged and mad, some have a heart attack and suddenly die, some [see] through a variety of inauspicious signs [their] wealth, accumulated possessions and descendants disappear without leaving any trace, like a pond whose feeding river has ceased, whereas some [find it] difficult to achieve anything in successive lifetimes.”[16]

Although Trijang Rinpoche (1900-1981), one of Pabongkha Rinpoche’s famous disciples, had a more moderate view on other traditions than Pabongkha, nevertheless “he continued to regard the deity (Dorje Shugden) as a severe and violent punisher of inclusively orientated Gelug practitioners.”[67] Trijang Rinpoche, as the Junior Tutor of HH the Dalai Lama introduced the Dorje Shugden practice to the Dalai Lama in 1959. Some years later, the 14th Dalai Lama recognized that this practice is in conflict with the state protector Pehar and with the main protective goddess of the Gelug tradition and the Tibetan people, Palden Lhamo (dPal ldan lha mo), and that this practice is also in conflict with his own open and ecumenical (Rimé) approach and religious and political responsibilities. After the publication of Zemey Rinpoche’s sectarian text The Yellow Book on Shugden, he spoke publicly against Dorje Shugden practice and distanced himself from it.

The Conflict in the West

Geshe Kelsang Gyatso and New Kadampa Tradition

These ideological, political and religious views on an exclusive/inclusive approach or belief were brought to the west and were at large expressed in the west by the conflicts (1979-1984)[68] between Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, who developed at Manjushri Institute an ever increasing ‘exclusive’ approach,[69] and Lama Yeshe, who had a more ‘inclusive’ approach[70] and had invited Geshe Kelsang in 1976 to England at his FPMT centre and later lost this centre, Manjushri Institute, to Geshe Kelsang and his followers.[71]

However, these conflicts didn’t appear to the public. But the issue about the nature of Dorje Shugden became visible to the broader public by the New Kadampa Tradition’s (NKT) media-campaign (1996-1998) on Dorje Shugden against the 14th Dalai Lama, after the Dalai Lama has rejected and spoken out against this practice.[72] He has described Shugden as an evil and malevolent force, and argued that other Lamas before him had also placed restrictions on worship of this spirit.[72] Geshe Kelsang teaches that the deity Dorje Shugden is the Dharma protector for the New Kadampa Tradition and is a manifestation of the Buddha[72] and commented that this practice was taught him and the Dalai Lama by Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, that’s why, he concludes, they cannot give it up, otherwise they would break their Guru’s pledges.

In 1996, Geshe Kelsang and his disciples started to denounce the Dalai Lama in public of being a “ruthless dictator” and “oppressor of religious freedom”,[73] they organized demonstrations against the Dalai Lama in the UK (later also in the USA, Swiss and Germany) with slogans like “Your smiles charm Your actions harm”.[74] Geshe Kelsang and the NKT accused the Dalai Lama of impinging on their religious freedom and of intolerance,[75] and further they accused the Dalai Lama “of selling out Tibet by promoting its autonomy within China rather than outright independence, of expelling their followers from jobs in Tibetan establishments in India, and of denying them humanitarian aid pouring in from Western countries.”[72] Newspapers like The Guardian (Britain), The Independent (Britain), The Washington Post (USA), The New York Times (USA), Die TAZ (Germany) as well as other newspapers in different countries picked up the hot topic and published articles, reported about the conflict and especially the Shugden Supporters Community (SSC) and NKT. Besides these and CNN, the BBC and Swiss TV also reported in detail about these conflicts. The Guardian: “A group calling itself the Shugden Supporters Community – the majority of whose members are also NKT – has mounted a high-profile international campaign, claiming the Dalai Lama’s warnings against Dorje Shugden amount to a ban which denies religious freedom to the Tibetan refugee settlements of India. And NKT members have been handed draft letters to send to the Home Secretary asking for the Dalai Lama’s visa for the UK to be cancelled, arguing that he violates the very human rights – of religious tolerance and non-violence – which he has spent his life promoting.”[77] According to The Independent: “The view from inside the Shugden Supporters Community was almost a photographic negative of everything the outside world believes about Tibet and the Dalai Lama.”[78] Regarding the facts SSC (NKT) spread, The Independent said: “It was a powerful indictment, flawed only by the fact that almost everything I was told in the Lister house was untrue.”[78] In support of the NKT, the SSC published a directory of supporters (“Dorje Shugden Supporter List”), which included monasteries in India and other non-NKT Western-based centers, associated with known Tibetan Buddhist teachers. This list was part of the second press pack, released on 10 July 1996.[79] The listing of western-based groups and their Buddhist teachers may have been misleading as well.[79] Lama Gangchen Rinpoche for instance did not express his support for the campaign and was shocked to hear that he had been listed as a supporter.[79] Also Dagyab Kyabgön Rinpoche was put on the list without he had been asked for and even after he had complained to Geshe Kelsang Gyatso individually, his name and his organisation’s name weren’t removed from the list.[80] According to a German Buddhist Magazine, there were a number of names of Tibetan teachers and their organisation on the list who never gave their support or even were asked for it.[80]

As a result of the aggressive campaign, the NKT was faced with hostile press articles. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. commented: “The demonstrations made front-page news in the British press, which collectively rose to the Dalai Lama’s defense and in various reports depicted the New Kadampa Tradition as a fanatic, empire-building, demon-worshipping cult. The demonstrations were a public relations disaster for the NKT, not only because of its treatment by the press, but also because the media provided no historical context for the controversy and portrayed Shugden as a remnant of Tibet’s primitive pre-Buddhist past.”[81]

Geshe Kelsang Gyatso and his followers are convinced that the actions of the Dalai Lama in that dispute are solely politically motivated. In November 2002, he wrote in an open letter to The Washington Times: “in October 1998 we decided to completely stop being involved in this Shugden issue because we realized that in reality this is a Tibetan political problem and not the problem of Buddhism in general or the NKT.”[82] However, according to the The Sydney Morning Herald, Australia, in September 2002, NKT members held a news conference at which they said: “The Dalai Lama and his soldiers in Dharamsala are creating terror in Tibetan society by harassing and persecuting people like us. We cannot take it lying down for long.”[76]

A main feature of the exclusive approach among Shugden devotees is a total reliance on one Guru and his tradition, which was fortified by Pabongkha Rinpoche by the Life Entrusting (srog gtad) practice on Shugden. Although “Pa-bong-ka had an enormous influence on the Ge-luk tradition that cannot be ignored in explaining the present conflict. He created a new understanding of the Ge-luk tradition which focused on three elements: Vajrayogini as the main meditational deity (yi dam), Shuk-den as the protector, and Pa-bong-ka as the guru.”[83] The imperative of total reliance on one Guru was enhanced once more by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso in the west – although the Life Entrusting (srog gtad) ceremony is not given by him. According to Geshe Kelsang, the student must “be like a wise blind person who relies totally upon one trusted guide instead of attempting to follow a number of people at once”[84] and “Experience shows that realizations come from deep, unchanging faith, and that this faith comes as a result of following one tradition, purely relying upon one Teacher, practicing only his teachings, and following his Dharma Protector.”[85] According to Kay: “Even the most exclusively orientated Gelug lamas, such as Phabongkha Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche, do not seem to have encouraged such complete and exclusive reliance in their students as this.”[86]

In 2006, Geshe Kelsang claimed in public, during the annually NKT summer festival, that:

Dorje Shugdän is a Dharma Protector who is a manifestation of Je Tsongkhapa. Je Tsongkhapa appears as the Dharma Protector Dorje Shugdän to prevent his doctrine from degenerating.

Je Tsongkhapa himself takes responsibility for preventing his doctrine from degenerating or from disappearing… To do this, since he passed away he continually appears in many different aspects, such as in the aspect of a Spiritual Teacher who teaches the instructions of the Ganden Oral Lineage. Previously, for example, he appeared as the Mahasiddha Dharmavajra and Gyälwa Ensapa; and more recently as Je Phabongkhapa and Kyabje Trijang Dorjechang. He appeared in the aspect of these Teachers.[87]

Other Tibetan Lamas

There are other Tibetan Gelug-Lamas in the west who follow the Dorje Shugden practice like Gonsar Rinpoche (Swiss), Dagom Rinpoche (Nepal/USA), Panglung Rinpoche (Germany), Gyalzar Rinpoche (Swiss), Kundeling Rinpoche (India/Netherlands), and Lama Gangchen Rinpoche (Italy), all of them with their own approach and attitude but more moderate than Geshe Kelsang and NKT. Except Kundeling Rinpoche who is not officially recognized by the Dalai Lama as a Tulku, the other Lamas do still respect the 14th Dalai Lama but cannot accept his reasoning. A main argument of Dagom Rinpoche and Gonsar Rinpoche is they do not really understand the Dalai Lama advising against the practice. Gonsar Rinpoche said, “I have spent many years in exile and have a great reverence for His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, but now he is abusing our freedom by banning Shugden. It makes me very sad… We are not doing anything wrong; we are just keeping on with this practice, which we have received through great masters. I respect His Holiness very much, hoping he may change his opinion… I cannot accept this ban on Shugden. If I accept this, then I accept that all of my masters, wise great masters, are wrong. If I accept that they are demon worshippers, then the teachings are wrong, everything we believe in is wrong. That is not possible.”[88] Geshe Kelsang also argued in the same way when he said: “If the practice of Dorje Shugden is bad, then definitely we have to say that Trijang Rinpoche is bad, and that all Gelugpa lamas in the Dalai Lama’s own lineage would be bad.”[89] Contrary to this point of view, the Dalai Lama stated: “I am of the opinion that Phabongkha and Trijang Rinpoche’s promotion of the worship of Dholgyal was a mistake. But their worship represents merely a fraction of what they did in their lives. Their contributions in the areas of Stages of the Path, Mind Training and Tantra teachings were considerable. Their contribution in these areas was unquestionable and in no way invalidated by involvement with Dholgyal… My approach to this issue (i.e. differing on one point, whilst retaining respect for the person in question) is completely in line with how such great beings from the past have acted.”[90]

However, from the point of view of many of the Shugden followers it is a painful dilemma. But it has to be stated that although Pabongkha Rinpoche “married the cult of the protective deity Dorje Shugden to the idea of Gelug exclusivism and employed against other traditions as well as against those within the Gelug who had eclectic tendencies”,[91] lamas like Lama Gangchen Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe (who in the past also practiced Dorje Shugden) nevertheless follow an inclusive approach. It has to be further stated that an exclusive approach does not necessarily include the idea of having a sectarian view.[92]

Kay states: “Examples of such lamas, who have taught in the West, include Geshe Rabten, Gonsar Rinpoche, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, Lama Thubten Yeshe, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Geshe Thubten Loden, Geshe Lobsang Tharchin, Lama Gangchen and Geshe Lhundup Sopa. It should be remembered that their association with this particular lineage-tradition does not necessarily mean that they are exclusive in orientation or devotees of Dorje Shugden. Some lamas, like Geshe Kelsang and the late Geshe Rabten, have combined these elements, whereas others, like Lamas Yeshe and Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Gangchen, came into exile with a commitment to the protector practice but not to its associated exclusivism.”[93] Lama Gangchen Rinpoche for instance, a Gelug Tulku and close disciple of Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, had been even called metaphorically the “motherland of syncretism”.[94]

Obedience towards the Guru

Because a main argument in the conflict on the side of the Shugden followers is that their Gurus (Lamas) (e.g. Pabongkha Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche) revealed the Shugden practice and gave obligations on it, one has to follow it, whereas the Shugden opponents in the Gelug school cite Buddha in the Kalama Sutra and Je Tsongkhapa, the Gelug founder, who said one should not follow “if it is an improper and irreligious command”, which is based on the Vinaya Sutra: “If someone suggests something which is not consistent with the Dharma, avoid it.”[95] They refer to the sectarian nature of the Shugden practice which is seen by them as a contradiction to Buddhist ethics, and one can also sum up the conflict as the religious scientist Michael von Brück (LM University, Munich) has done:

“We can conclude that the present controversy reveals the contradiction between the imperative of critically establishing the validity of (one’s own) opinions and the obedience towards the Lama (Guru)”[96]

Summary

By these examinations, it becomes clear that the religious and political conflict around Dorje Shugden is mainly based on a polarisation of an exclusive/inclusive approach. According to Kay: “This classical inclusive/exclusive division has largely been articulated within the exiled Tibetan Buddhist community through the dispute concerning the status and nature of the protective deity Dorje Shugden.”[97] The exclusive/inclusive approach can be traced back to Tsongkhapa’s and Khedrub Jey’s different approaches and the frictions deriving from these two different approaches are a part of the Gelug history, transferred to the west and are related strongly to personal, philosophical, political, regional and institutional views, interests and struggles.

Arguments for and against

Arguments and Buddhist teachers who advised against Dorje Shugden practice

Views of the XIVth Dalai Lama

The XIVth Dalai Lama is asking people who want to take initiation from him to let go of this practice and this deity[98], and gives three main reasons for advising against the propitiation of Dholgyal (Shugden):

“Such practices degenerate the profound and vast teachings of Buddhism, wherein our ultimate refuge is the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. While the profound teachings of the Buddha are based on the two truths and the Four Noble Truths, the appeasing and propitiating of Dholgyal, to the extent it is done by those who do this practice, degenerate the Buddhist practice into a form of spirit worship.

It goes against His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s non-sectarian approach especially within the Tibetan Buddhist traditions. His Holiness himself practices teachings from the other traditions such as Nyingma, Sakya and Kagyu simultaneously with the Geluk tradition and encourages others to do the same. However, the practice of Dholgyal is extremely sectarian.

The Dholgyal spirit has a long history of antagonistic attitude to the Dalai Lamas and the Tibetan Government they head since the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama. Throughout that period, it has also been very controversial in both the Geluk and Sakya traditions. In fact, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama and the Great Thirteenth Dalai Lama, as well as many other prominent Tibetan lamas have categorically stated the harmful effects of this practice and have advised against the practice and propitiation of Dholgyal.”[99]

He is stating further:

“The ones who want to keep their practice of Shugden should not attend any further events or ceremonies in which a teacher-disciple relationship is established with me. This is something each person has to decide for him/herself. Each person has to take care of this themselves. From my side, I don’t want this relationship to be established if it is the case that the person is keeping up the Shugden practice. I myself would engage in contradiction to the commitments I have had towards the previous Dalai Lamas, especially toward the 5th Dalai Lama, and therefore I request that if any of you are practicing Shugden for you not to attend the initiations. I have explained the reasons why I am against the veneration of Shugden and given my sources in a very detailed manner.”[98]

Statement by the Previous (100th) Ganden Tripa

The previous (100th) Ganden Tripa, Lobsang Nyingma Rinpoche, stated:

“If it [Shugden] were a real protector, it should protect the people. There may not be any protector such as this, which needs to be protected by the people. Is it proper to disturb the peace and harmony by causing conflicts, unleashing terror and shooting demeaning words in order to please the Dharmapala? Does this fulfill the wishes of our great masters? Try to analyze and contemplate on the teachings that had been taught in the Lamrim [stages of path], Lojong [training of mind] and other scriptural texts. Does devoting time in framing detrimental plots and committing degrading act, which seems no different from the act of attacking monasteries wielding swords and spears and draining the holy robes of the Buddha with blood, fulfill the wishes of our great masters?”[100]

and

“The Mahayana teachings advocate an altruistic attitude of sacrificing few for the sake of many. Thus why is it not possible for one, who acclaims oneself to be a Mahayana, to stop worshipping these dubious gods and deities for the sake and benefit of the Tibetans in whole and for the well-being of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. In the Vinaya [Buddhist code of discipline], it is held that since a controversial issue is settled by picking the mandatory twig by “accepting the voice of many by the few” the resolution should be accepted by all. As it has been supported by ninety five percent it would be wise and advisable for the remaining five percent to stop worshipping the deity keeping in mind that there exists provisions such as the four Severe Punishments [Nan tur bzhi], the seven Expulsions [Gnas dbyung bdun] and the four Convictions [Grangs gzhug bzhi] in the Vinaya [Code of Discipline].”[100]

Gelug Opponents

According to Lama Zopa Rinpoche “Some people think that the practice of Shugden prevents Lama Tsong Khapa’s teachings from degenerating and promotes their development. But there have been many Gelug lamas who without practicing Shugden, spread Buddhadharma, spread the stainless teaching of Lama Tsong Khapa like the sky.” He refers to the 14th, 13th Dalai Lamas, Ling Rinpoche and Kachen Yeshe Gyaltsen, the latter “a great, well-known Tibetan lama who wrote many, many teachings and not only didn’t practice Shugden but also advised against the practice.”[101]

Lama Zopa Rinpoche states:

“Purchog Jampa Rinpoche, a very high lama of Sera Je Monastery and an incarnation of Maitreya Buddha, wrote against the practice of Shugden in the Monastery’s constitution. Jangkya Rölpa’i Dorje and Jangkyang Ngawang Chödrön, who wrote many excellent texts, also advised against this practice, as did Tenpa’i Wangchuk, the Eighth Panchen Lama, and Losang Chökyi Gyaltsen, the Fourth Panchen Lama, who composed the Guru Puja and wrote many other teachings, and Ngulchu Dharmabhadra. All these great lamas, and many other highly accomplished scholars and yogis who preserved and spread the stainless teaching of Lama Tsong Khapa, recommended that Shugden not be practiced.”[101]

Opponents from other Tibetan Buddhist schools

According to The Dolgyal Research Committee (Tibetan Government in Exile), prominent opponents include not only the 5th, 13th and current Dalai Lamas but also the 5th and 8th Panchen Lamas, Dzongsar Khyentse Chokyi Lodro, the 14th and 16th Karmapas among others.[102] Another source states that Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, a Dzogchen master, “has been insisting on the importance of failing to appreciate the danger inherent in such cults”.[10] Opponents include Mindrolling Trichen Rinpoche[103], former head of the Nyingma school, and Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche, who is head of 25 monasteries in Bhutan, and stated: People who practice Shugden “will get many money, many disciples and then many problems.”[104]

Arguments by followers of Shugden

Shugden supporters responded point-by-point as follows:

- The statement that Dorje Shugden is a worldly spirit is unsubstantiated and contradicts the view of many spiritual masters of the Gelug tradition who hold him to be a manifestation of the Wisdom Buddha.

- Furthermore, the essential Mahayana Buddhist doctrine of the emptiness of persons requires that one should not attribute inherently existent qualities to any being. Thus, Shugden like any other being has the qualities that one’s own mind sees in him.

- Prior to instigating this ban, there was no history of disharmony between practitioners of Dorje Shugden and other traditions – it is the ban itself that is a manifestation of sectarianism.

- There is no evidence to support the claims that the Dalai Lama’s health and the interests of the Tibetan people have been affected.

- Divination is not a reliable means of deciding such issues. Furthermore, evidence from oracles is not admissible either.

- The Dalai Lama might claim that his teachers agreed to him stopping the practice, but in reality they had no choice but to accept, as to go against the Dalai Lama results in grave consequences. It is said that Trijang Rinpoche in particular was ‘very disappointed’ that the Dalai Lama abandoned his practice of Dorje Shugden.

Pro-Dorje Shugden Gelug teachers have asked the Dalai Lama to present valid reasons supporting these claims and, in the absence of any response, have continued to engage in the practice.

Shugden supporters accuse the Dalai Lama of “banning” them, with the following specifics:

- Such practitioners are discouraged from attending teachings by the Dalai Lama.

- Practitioners of Dorje Shugden are not allowed to hold public office within the Tibetan Government in Exile.

- Many monasteries and individuals publicly engaging in the practice have been pressed to stop.

- The official “ban” on this practice has sparked debate within the Tibetan community and widespread public pressure upon those maintaining the practice.

Shugden-followers claim there is documentary evidence to support this. The Tibetan Government in Exile rejects the claims (2)-(4).[105]

Introduction to Dorje Shugden by Kelsang Gyatso

“Buddhas have manifested in the form of various Dharma Protectors, such as Mahakala, Kalarupa, Kalindewi, and Dorje Shugden. From the time of Je Tsongkhapa until the first Panchen Lama, Losang Chökyi Gyaltsän, the principal Dharma Protector of Je Tsongkhapa’s lineage was Kalarupa. Later, however, it was felt by many high Lamas that Dorje Shugden had become the principal Dharma Protector of this tradition.

There is no difference in the compassion, wisdom, or power of the various Dharma Protectors, but because of the karma of sentient beings, one particular Dharma Protector will have a greater opportunity to help Dharma practitioners at any one particular time.

We can understand how this is so by considering the example of Buddha Shakyamuni. Previously the beings of this world had the karma to see Buddha Shakyamuni’s Supreme Emanation Body and to receive teachings directly from him.

These days, however, we do not have such karma, and so Buddha appears to us in the form of our Spiritual Guide and helps us by giving teachings and leading us on spiritual paths. Thus, the form that Buddha’s help takes varies according to our changing karma, but its essential nature remains the same.

Among all the Dharma Protectors, four-faced Mahakala, Kalarupa, and Dorje Shugden in particular have the same nature because they are all emanations of Manjushri.

However, the beings of this present time have a stronger karmic link with Dorje Shugden than with the other Dharma Protectors. It was for this reason that Morchen Dorjechang Kunga Lhundrup, a very highly realized Master of the Sakya tradition, told his disciples, “Now is the time to rely upon Dorje Shugden.” He said this on many occasions to encourage his disciples to develop faith in the practice of Dorje Shugden.

We too should heed his advice and take it to heart. He did not say that this is the time to rely upon other Dharma Protectors, but clearly stated that now is the time to rely upon Dorje Shugden. Many high Lamas of the Sakya tradition and many Sakya monasteries have relied sincerely upon Dorje Shugden.

In recent years the person most responsible for propagating the practice of Dorje Shugden was the late Trijang Dorjechang, the root Guru of many Gelugpa practitioners from humble novices to the highest Lamas. He encouraged all his disciples to rely upon Dorje Shugden and gave Dorje Shugdän empowerments many times.

Even in his old age, so as to prevent the practice of Dorje Shugdän from degenerating he wrote an extensive text entitled Symphony Delighting an Ocean of Conquerors, which is a commentary to Tagpo Kelsang Khädrub Rinpoche’s praise of Dorje Shugden called Infinite Aeons.”[106]

References

Kay, David N. (2004). Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantation, Development and Adaptation – The New Kadampa Tradition (NKT), and the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives (OBC), London and New York, ISBN 0-415-29765-6, Routledge

Martin A. Mills (2003). Human Rights in Global Perspective: Anthropological Studies of Rights, Claims and Entitlements edited by Richard A. Wilson Jon P. Mitchell, ISBN: 0203506278, Routledge

Dreyfus, George (1999). The Shuk-Den Affair: Origins of a Controversy

Bunting, Madeleine (1996). Shadow boxing on the path to Nirvana, The Guardian – London

NOTES

1. BBC, The New Kadampa Tradition, [1]

2. Kay, David N. (2004). Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantation, Development and Adaptation – The New Kadampa Tradition (NKT), and the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives (OBC), London and New York, ISBN 0-415-29765-6, page 46

3. Kay : 2004, 47

4. Kay : 2004, 47

5. Kay : 2004, 47

6. Kay page 230

7. Kay : 2004, 47

8. Letter to the Assembly of Tibetan Peoples Deputies, Sakya Trizin, June 15 1996, Archives of ATPD in von Brück; Michael: Religion und Politik im Tibetischen Buddhismus. Kösel Verlag, München 1999, ISBN 3-466-20445-3, page 184

9. interview, July 1996, Kay page 230

10. a b c “A Spirit of the XVII Secolo”, Raimondo Bultrini, Dzogchen Community published in Mirror, January 2006,

11. See Interview in the Documentary Film at: Official Web Page of the Dalai Lama, http://www.dalailama.com/page.132.htm

12. Austria Buddhist magazine “Ursache und Wirkung”, July 2006, page 73

13. Nebesky-Wojkowitz 1956: 3

14. Kay 2004: 73

15. David N. Kay: Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantation, Development and Adaptation, London and New York, published by RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 0-415-29765-6, page 48

16. Dreyfus : 1999 – this is taken from a revised version of an essay published earlier in the Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (Vol., 21, no. 2 [1998]:227-270), see: The Shuk-Den Affair: Origins of a Controversy

17. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 55

18. “‘Jam mgon rgyal ba’i bstan srung rdo rje shugs ldan gyi ‘phrin bcol phyogs bsdus bzhugs so”, pages 33-37. Sera Me Press (ser smad ‘phrul spar khang), 1991.

19. “‘Jam mgon rgyal ba’i bstan srung rdo rje shugs ldan gyi ‘phrin bcol phyogs bsdus bzhugs so”, pages 31-33. Sera Me Press (ser smad ‘phrul spar khang), 1991.

20. Georges Dreyfus, Williams College, The Shuk-Den Affair: Origins of a Controversy, 1999

21. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 65

22. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 55

23. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 56

24. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 56

25. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 56

26. Mumford 1989:125-126

27. Mills, Martin A, Human Rights in Global Perspective, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30410-5, page 56

28. Dreyfus : 1999

29. Official Homepage of the Dalai Lama, http://www.dalailama.com/page.153.htm

30. Official Dalai Lama Homepage, [2]

31. Official Dalai Lama Homepage, [3]

32. Official Dalai Lama Homepage, [4]

33. Austria Buddhist magazine “Ursache und Wirkung”, July 2006, page 73

34. Kay: 2004, Dreyfus : 1999

35. Kay: 2004, page 43; Dreyfus : 1999; Chagdug Tulku “Der Herr des Tanzes” (“Lord of the Dance: Autobiography of a Tibetan Lama”), ISBN 3896201204 : page 133

36. Interview with Tashi Wangdi, David Shankbone, Wikinews, November 14, 2007.

37. CESNUR, [5]

38. Interview with Tashi Wangdi, David Shankbone, Wikinews, November 14, 2007.

39. Letter to the Indian Prime Minister by Dorje Shugden Devotees Charitable and Religious Society and Shugden Supporters Community (SSC), [6]

40. Amnesty International’s position on alleged abuses against worshippers of Tibetan deity Dorje Shugden, AI Index: ASA 17/14/98 June 1998